【推文】Yuri Bezmenov's Ghost - Descartes gave Western thought the cogito, stressing subjective...

連結

原推文 - x.com/ne_pas_couvrir...

Thread Reader App版本(一頁版本) - threadreaderapp.com/...

原文及個人翻譯

🧵Descartes gave Western thought the cogito, stressing subjective certainty & challenging external authority/objectivity. This seeded the idea that liberation starts with inward reflection, which then let ppl see oppressive orders as constructs to be unmade→opening later critiques of property, power & identity.

笛卡爾為西方思想帶來了「我思故我在」的概念,強調主觀的確定性,並挑戰外在權威和客觀性。這為解放從內省開始的觀念埋下了種子,讓人們能將壓迫性的秩序視為可以解構的建構物,進而開啟了對財產、權力和身份的後續批判。

Rousseau exposed how property & society "chain" (man is born free, but everywhere, chains) human freedom, urging rebellion against inequality. He saw civilization corrupting natural liberty, igniting a quest for autonomy that radicals embraced. But attempts to unify under universal ideals often clashed with deep-seated ethnic loyalties & tensions between collective will & individual rights.

盧梭揭露了財產和社會如何「束縛」人類的自由(人生來自由,卻處處受束縛),呼籲反抗不平等。他認為文明腐化了天生的自由,點燃了激進分子擁抱的自主追求。然而,在普遍理想下統一的嘗試往往與根深蒂固的民族忠誠相衝突,集體意志和個人權利之間的緊張關係也隨之出現。

Kant -reason frees us from dogma but also confines us within our own lens, revealing hidden frameworks shaping experience. This duality fueled later emancipatory thought, as people asked if they were blind to structural oppression. Kant’s critique laid a foundation for later efforts to expose & transform unseen power.

康德認為理性讓我們從教條中獲得自由,但也將我們局限在自己的視角中,揭示了塑造經驗的隱藏框架。這種雙重性為後來的解放思想提供了動力,人們開始質疑自己是否對結構性壓迫視而不見。康德的批判為後來揭露和轉變看不見的權力奠定了基礎。

Hegel -The ol' dialectical method here is abstract idea meets its negation and is sublated into a richer, concrete unity. He introduced the concept of alienation and the Volksgeist, the unique spirit of each people evolving through history. His dialectic applies across these spaces, showing how concepts, natural laws, & human consciousness evolve. In his 'philosophy of history,' Geist realizes itself through human activities, moving society toward its highest ethical realization within the state, where individual freedom & communal good reconcile in rational, ethical life (Sittlichkeit). Plus, his ideas on recognition, esp. via the master-slave dialectic, show self-consciousness emerging through social interaction.

黑格爾在這裡使用了辯證法,抽象的概念與它的否定相會,並轉化為更豐富的具體統一。他引入了異化和民族精神(Volksgeist)的概念,即每個民族在歷史中獨特的精神。他的辯證法適用於這些空間,展示了概念、自然法則和人類意識如何演變。在他的《歷史哲學》中,精神通過人類活動實現,推動社會向國家內最高道德實現邁進,個體自由與集體福祉在理性道德生活中和解。此外,他的認可思想,尤其是通過主奴辯證法,展示了自我意識通過社會互動出現。

Moses Hess transformed Descartes’s "I think, therefore I am" into "We do, therefore we are," shifting from individual certainty to collective action. Influenced by Rousseau, he argued that societies must harness their creative power to dismantle oppressive chains. Building on Kant’s insight about hidden frameworks, Hess demonstrated how economic & cultural forces shape consciousness, obscuring alienation. He applied Hegel’s dialectic to social conflicts over property, money, & labor (material turn), insisting that alienation is a lived, material experience. This synthesis paved the way for Marx’s materialist analysis, emphasizing that genuine freedom arises when thought & action unite in praxis.

So Hess bridged Descartes, Rousseau, Kant, & Hegel with Marx’s critique of capitalism, promoting a vision of collective emancipation by reclaiming social conditions.

摩西·赫斯將笛卡爾的「我思故我在」轉化為「我們行動故我們存在」,從個體確定性轉移到集體行動。受盧梭影響,他認為社會必須利用創造力量來拆除壓迫的鎖鏈。基於康德對隱藏框架的洞察,赫斯展示了經濟和文化力量如何塑造意識,模糊了異化。他將黑格爾的辯證法應用於財產、金錢和勞動的社會衝突(物質轉變),堅持異化是一種物質的、生活的體驗。這種綜合為馬克思的物質主義分析鋪平了道路,強調真正的自由源於思想和行動在實踐中的團結。

赫斯通過將笛卡爾、盧梭、康德和黑格爾的思想與馬克思對資本主義的批判相結合,促進了社會條件的再造,為集體解放鋪平了道路。

However, their paths diverged in focus & scope. While Marx continued developing a universal framework centered on class struggle and global emancipation, Hess reoriented his approach. Inspired by Hegel's Volksgeist, Hess integrated the idea of a distinct spiritual and cultural ethnos into his consciousness-raising goals. See Hess's work "Rome and Jerusalem,"

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1878453333179937131

然而,他們的道路在焦點和範圍上出現了分歧。馬克思繼續發展以階級鬥爭和全球解放為中心的普遍框架,而赫斯重新調整了他的方法。受黑格爾民族精神(Volksgeist)的啟發,赫斯將獨特的精神和文化民族概念融入了他的提高意識目標中。請參考赫斯的作品《羅馬與耶路撒冷》。

Marx - Using Hegel & Hess's on alienation, he expanded it bigly within the critique of capitalism, saying that the recognition of this alienation by the proletariat could lead to the development of true class ̷g̷n̷o̷s̷i̷s̷ consciousness... which would in turn dismantle the ̷p̷r̷i̷s̷o̷n̷ exploitative systems of wage labor and private property.

Building upon Descartes (subjective certainty), through Rousseau's (societal 'chains' on human freedom), Kant (frameworks that shape our understanding), & integrating Hegel's dialectical method with Hess's material turn, Marx synthesized a materialist dialectic. Here, economic conditions are the primary drivers of social relations & consciousness. Marx posited that the proletariat, by recognizing their collective alienation from the means of production (a concept he deepened from Hess's insights) would gain a ̷g̷n̷o̷s̷i̷s̷ self-awareness of their exploitation, sparking revolutionary action. His vision was one of ̷G̷n̷o̷s̷t̷i̷c̷i̷s̷m̷ global emancipation, where communal ownership of the means of production would supplant capitalist structures, thereby eradicating class distinctions & free humanity from the ̷d̷e̷m̷i̷u̷r̷g̷e̷ shackles of material alienation.

Underlying this ̷r̷e̷l̷i̷g̷i̷o̷n̷ is the belief that the transformation of economic structures would lead to a transformation in human consciousness and societal organization, fulfilling the potential for universal human liberation. But it's totally material and not ideal, guys.

馬克思利用黑格爾和赫斯對異化的論述,在對資本主義的批判中大大擴展了這一概念,認為無產階級認識到這種異化可以導致發展出真正的階級意識(=~靈知gnosis),進而拆除剝削的工資勞動和私有財產體系=監獄。

馬克思綜合了笛卡爾的主觀確定性、盧梭對社會「鎖鏈」束縛人類自由的觀點、康德的框架塑造理解的方式,並融合了黑格爾的辯證法和赫斯的物質轉變。他合成了一種物質主義辯證法,其中經濟條件是社會關係和意識的主要驅動因素。馬克思認為,無產階級通過認識到他們從生產資料中受到的集體異化(這個概念是從赫斯的洞察中深化的),將獲得對剝削的自我意識(=~靈知gnosis),從而引發革命行動。他的願景是一種全球解放(=~靈知派Gnosticism),其中生產手段被集體所擁有將取代資本主義結構,從而消除階級區別,並使人類擺脫物質異化的枷鎖(=~造物主demiurge)。

這種信仰(=~宗教)的基礎在於,經濟結構的轉變將導致人類意識和社會組織的轉變,實現普遍人類解放的潛力。但這完全是物質上的,不是理想上的,朋友們。

In anticipation for the butthurt Marxists, 'Ol Dirty Santa expands on the labor theory of value where labor is the source of all wealth, & surplus value extracted from workers constitutes capitalist profit, revealing inherent exploitation. Dirty, Lazy Santa argues that society's mode of production shapes laws, culture, & politics, driving historical development through class struggle between oppressors & oppressed. Marx sees the state as a tool of class rule under the social prison of capitalism, proposing a transitional phase, the dictatorship of the proletariat (lol), to dismantle capitalist structures & will just wither away on its own to to a stateless, classless society (lawl).

'Ol Dirty Santa also advocates for internationalism, thinking workers globally share a common fight against bourgeois dominance. Marx also critiques ideology, seeing religion, law, and education as mechanisms that perpetuate false consciousness and maintain the capitalist status quo. With Engels the Enabler, he developed dialectical materialism, which 'analyzed' contradictions within capitalism and the role of technology in intensifying class conflict, suggesting that these dynamics make capitalism obsolete (lawl). Later, leftist dummies divined that his work hints at ecological concerns through the concept of the metabolic rift (see link)https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1693045691377946972

預見到即將到來的馬克思主義者,髒老爹(馬克思)擴展了勞動價值理論,其中勞動是所有財富的源泉,從工人身上提取的剩餘價值構成了資本家的利潤,揭示了內在的剝削。髒懶老爹認為,社會的生產方式塑造了法律、文化和政治,通過壓迫者和被壓迫者之間的階級鬥爭推動歷史發展。馬克思認為國家是階級統治的工具,在資本主義的社會監獄下,他提出了一個過渡階段,即無產階級專政(哈哈),以拆除資本主義結構,並最終自行消亡,形成一個沒有國家和階級的社會(哈哈哈)。

髒老爹還倡導國際主義,認為全球工人共同對抗資產階級統治。馬克思也批評意識形態,認為宗教、法律和教育是延續虛假意識、維持資本主義現狀的機制。與恩格斯(Engels)這個助長者一起,他發展了辯證唯物主義,分析了資本主義內部的不矛盾和技術在加劇階級衝突中的作用,建議這些動態使資本主義過時(哈哈)。後來,左傾傻瓜們從他的作品中推斷出對生態問題的暗示,這體現在代謝裂痕的概念中(見鏈接)。

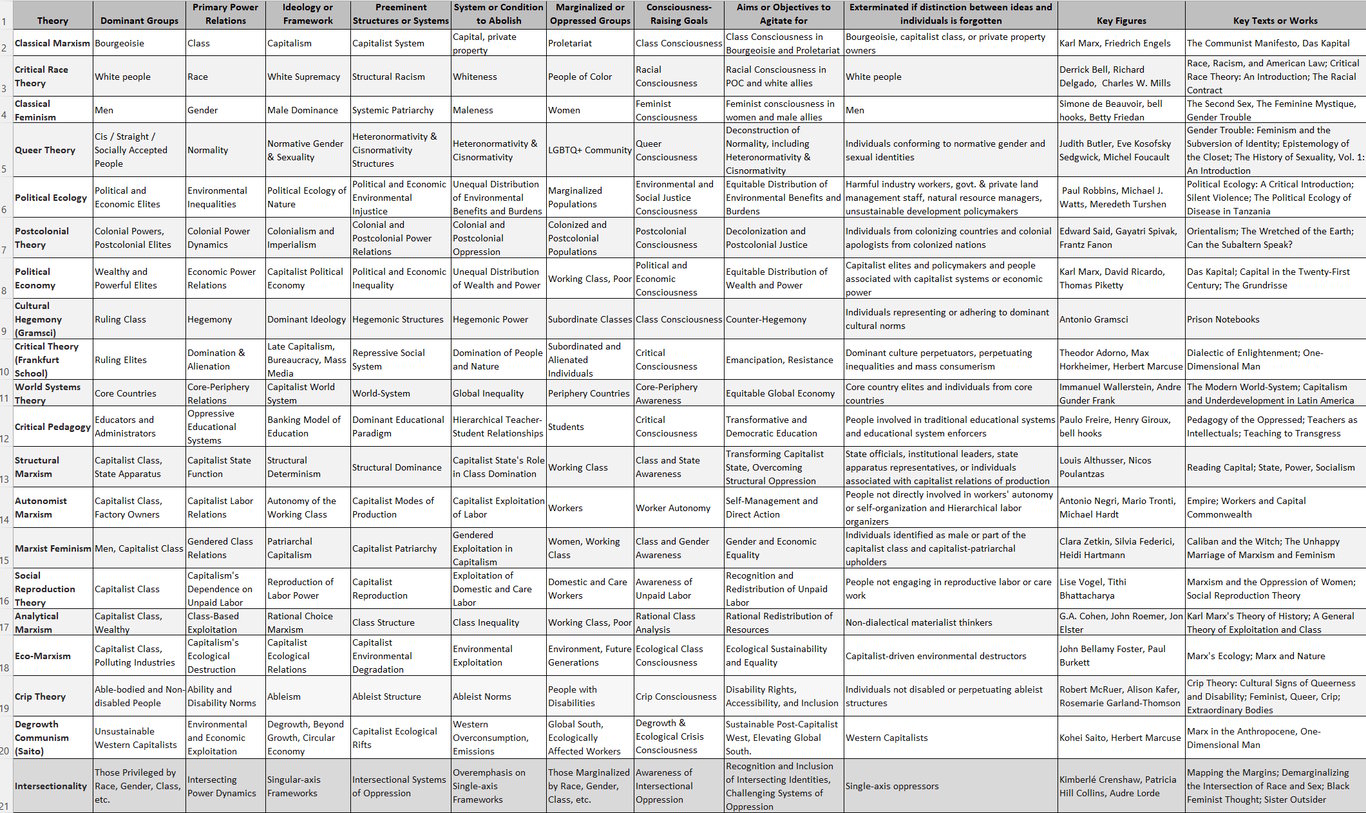

(順便貼連結中的圖但表格太大我懶得翻…)

Gramsci - In prison and butthurt over the West's refusal to try communism, built on the above by explaining how the ruling class keeps winning through cultural & ideological hegemony. Specifically, he analyzed how the ruling class maintains power in the capitalist West through cultural & ideological hegemony. He argued that institutions like media, law, religion, family & education in civil society shapes norms & consciousness, making bourgeois ideology seem natural. Gramsci argued that a direct assault on the state was less feasible in the West. Instead, he proposed a war of position: a slow, methodical struggle to build counter-hegemony by infiltrating civil society, which makes sense if you remember he was sitting in prison, writing about it.

Gramsci highlighted the need for ̷c̷o̷m̷m̷i̷e̷ ̷n̷e̷r̷d̷s̷ intellectuals from the working class to lead this cultural struggle & form a national-popular coalition that resonates with everyday people. He saw the state as protected by a 'trench' of civil society, which must be penetrated (bow-chicka-bow-bow) first. He introduced concepts like passive revolution, where reforms defuse revolutionary pressures without altering power, and the historical bloc, where diverse social groups unite under a shared ideology. Commie nerd fantasy-Cultural battles, aiming to transform society from within through education, media, & coalition-building well before confronting state power directly.

葛蘭西在監獄中,對西方拒絕嘗試共產主義感到不悅,他建立在上述理論基礎上,解釋了統治階級如何通過文化和意識形態的霸權來維持勝利。具體來說,他分析了統治階級如何通過媒體、法律、宗教、家庭和教育等公民社會機構來塑造規範和意識,使資產階級意識形態看起來是自然的。葛蘭西認為,直接攻擊國家在西方不太可行。相反,他提出了一場位置戰爭:一場緩慢、有條不紊的鬥爭,通過滲透公民社會來建立反霸權,這有道理,因為他當時坐在監獄裡,寫著這些。

葛蘭西強調了來自工人階級的知識分子(共產主義迷)領導這場文化鬥爭的必要性,並形成一個能與普通民眾共鳴的民族人民聯盟。他認為國家受到公民社會的「戰壕」保護,必須首先穿透它。他引入了被動革命的概念,即改革緩解了革命壓力,但沒有改變權力,以及歷史集團,即不同社會群體在共同意識形態下團結。

葛蘭西的共產主義迷幻想——文化戰爭,旨在通過教育、媒體和建立聯盟,在直接面對國家權力之前,從內部轉變社會。

Umlaut and accent enjoyer, György Lukács, like Gramsci, was concerned with why the West resisted communism. However, he had a different take, introducing reification-capitalism makes social relations appear fixed and natural-which he identified as a barrier to revolution in the West.

In "History & Class Consciousness," he urged the proletariat to grasp the totality of their conditions to break alienation (see above) and spark revolution. Drawing on Hegel, Lukács used the dialectical to show how capitalism ...mystifies reality.., obstructing the ...spontaneous formation of 'genuine' class consciousness (lol).

So, while Gramsci focused on cultural hegemony, Lukács talked about how capitalist society shapes consciousness through reification like an illusion, which for him explains Western resistance to communism & not because its garbage. Like most post Marxist theorists, both Gramsci and Lukács are similar, with both emphasizing ideology and consciousness but from distinct angles: Gramsci on cultural strategy, Lukács on reification and philosophical depth.

匈牙利人,喬治·盧卡奇(György Lukács),也對西方為何抵抗共產主義感到擔憂,但他有不同的觀點,引入了再商品化概念——資本主義使社會關係看起來固定和自然,他認為這是西方革命的障礙。

在《歷史與階級意識》中,他敦促無產階級理解他們條件的整體性,以打破異化(見上文)並點燃革命。盧卡奇利用黑格爾的辯證法來展示資本主義如何「神秘化」現實,阻礙「真正」階級意識的自然形成。

因此,雖然葛蘭西關注文化霸權,盧卡奇則討論資本主義社會如何通過再商品化來塑造意識,就像一種幻覺,這在他看來解釋了西方對共產主義的抵抗,而不是因為它垃圾。像大多數後馬克思主義理論家一樣,葛蘭西和盧卡奇都相似,都強調意識形態和意識,但從不同的角度:葛蘭西關注文化策略,盧卡奇關注再商品化和哲學深度。

The Frankfurt School - Part 1 (Max Horkheimer & Theodor Adorno)

Post-WWII, they were butthurt. As Jewish scholars, they'd seen revolutionary movements meant to negate capitalism's ills spiral into catastrophes. Fascism and Stalinism, they argued, weren't aberrations but the Enlightenment's dark offspring baked in. The negation of the negation that was supposed to lead to a Communist utopia failed and led to either Fascism or Ethno-socialism. They saw Nazism as a twisted negation of liberal capitalism's failures, not a step toward Marx's classless dream. Stalin's USSR, meanwhile, ditched internationalism after Korenizatsiya flopped, pivoting to Russian ethnos as a unifying force, sidelining Jews and others in purges.

Horkheimer and Adorno, scarred by these betrayals, fled to Golden-Age California, where they co-wrote Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), which was a takedown of modern reason gone wrong. Here, they argued that the very project of Enlightenment, which was supposed to liberate us through reason, backfired, produced new forms of domination culminating in fascism, Stalinism, a manipulative 'culture industry,' and mass consumer capitalism instead of true freedom. In other words, Ol' Kantian rationality and industrial progress didn't deliver a utopia; they gave us Hitler and Hollywood.

法蘭克福學派 - 第一部分(馬克斯·霍克海默和特奧多爾·阿多諾)

二戰之後,他們感到非常失望。作為猶太學者,他們目睹了本來旨在否定資本主義弊端的革命運動演變成災難。他們認為,法西斯主義和斯大林主義不是異端,而是啟蒙運動的黑暗後裔。本應引領到共產主義烏托邦的「否定之否定」失敗了,導致了法西斯主義或民族社會主義。他們將納粹主義視為對自由資本主義失敗的扭曲否定,而不是邁向馬克思無階級夢想的一步。同時,斯大林的蘇聯在本土化(Korenizatsiya)失敗後,拋棄了國際主義,轉向俄羅斯民族作為統一力量,在清洗中排斥猶太人和其他人。

霍克海默和阿多諾對這些背叛感到傷痛,逃往加州黃金時代,合著了《啟蒙辯證法》(1947年),這本書批評了現代理性走火入魔。他們認為,本應通過理性解放我們的啟蒙運動適得其反,產生了新的支配形式,最終導致法西斯主義、斯大林主義、操縱性的「文化工業」和大規模消費資本主義,而不是真正的自由。換句話說,老康德的理性與工業進步並沒有帶來烏托邦;它們給了我們希特勒和好萊塢。

Their big idea of "instrumental reason' says that Western reason got too obsessed with controlling nature and people. What does this mean.. think of science and tech not as paths to truth and liberty but as tools to dominate and turn humans into compliant cogs. Here, they were riffing off Weber's rationalization and Georg Lukacs's notion of reification (the idea that social relations under capitalism solidify into things, commodities that then control us by an "autonomy alien to man.")

Horkheimer and Adorno dialed all this up to 11: under late capitalism, everything, meaning from culture to consciousness, becomes commodified & 'fetishized,' trapping us in a shiny, unthinking consumer trance. They even coined the term "culture industry" for the mass production of art and entertainment, accusing Hollywood, pop music, and magazines of anesthetizing the masses much like religion or ideology did for old Karl Marx. (Adorno infamously hated jazz for being pseudo-individualistic, which is hilarious, considering how derivative his work is)

The irony is these theorists were intellectual magpies: they borrowed from Hegel's dialectics, Marx's critique of ideology, Freud's psychoanalysis (to analyze mass psychology), and Nietzsche's suspicion of modernity- all to explain why the modern world was looking more like a bureaucratic nightmare than an enlightened paradise.

他們的大概念「工具理性」認為,西方理性過度痴迷於控制自然和人。這意味著什麼?想像科學和技術不是通往真理和自由的道路,而是支配的工具,將人變成順從的齒輪。他們在這裡借鑒了韋伯的合理化和喬治·盧卡奇的再商品化概念(即資本主義下社會關係凝固成商品,然後通過一種「異化的人類自主性」控制我們)。

霍克海默和阿多諾將這些想法提升到極致:在後期資本主義下,從文化到意識,一切都成為商品化和「神聖化」的對象,讓我們陷入一個閃亮、不思考的消費迷幻狀態。他們甚至為大眾生產藝術和娛樂創造了「文化工業」一詞,指控好萊塢、流行音樂和雜誌麻木大眾,就像宗教或意識形態對老馬克思所做的那樣。(阿多諾臭名昭著地討厭爵士樂,認為它虛偽地個人主義,這很有趣,因為他的作品非常衍生。)

諷刺的是,這些理論家是知識界的喜鵲:他們借鑒了黑格爾的辯證法、馬克思的意識形態批判、弗洛伊德的精神分析(用於分析群眾心理)和尼采對現代性的懷疑——所有這些都用來解釋為什麼現代世界看起來更像一個官僚主義的噩夢,而不是啟蒙的天堂。

Horkheimer and Adorno knew they were in a bit of a bind b/c they were using reason to critique reason. Ever the butthurt mid-wit, Adorno even admitted this 'performative contradiction' of denouncing Enlightenment's totalitarian turn with Enlightenment's own tools. Yet, they saw no choice; philosophy itself had to become self-critical. In their view, earlier thinkers from Descartes to Kant put a sovereign rational subject at the center, & even progressive heirs like Rousseau or Marx couldn't prevent reason from mutating into domination. They extended Marx's ideology critique beyond the economy into every realm of culture and consciousness. And unlike Gramsci's relatively hopeful idea of cultural hegemony, Adorno and Horkheimer were pretty pessimistic that the working class (or anyone) could resist this new totalizing system. FYI - this was a point where they even parted ways with Lukacs's faith in the revolutionary proletariat.

The only hope, per Adorno, was a "negative dialectics." What this means is relentless criticism that refuses to be satisfied with false wholes. They call out the "false laughter" of TV audiences and the way Enlightenment's promise of freedom ends up as a dark joke. Contradiction was their thing. By highlighting how modern society creates new myths (like consumerism) even as it claims to be rational, these Frankfurt School founders set the stage for generations of radicals to question everything from Hollywood blockbusters to instrumental science. In short, Horkheimer and Adorno are the OGs of critical theory. Their legacy is a method of relentless, endless critique.I suppose we should take a second on their Authoritarian Personality study (1950), with its F-scale (F for fascism), which was their attempt to pin down why people fall for totalitarian traps. So, using Freudian lenses, they probed how repressed desires and social conformity breed fascist tendencies, a direct response to Nazi horrors. But they sidestepped how their beloved dialectic (here, the negation of the negation) kept landing on fascism, not communism. Instead of owning this, they externalized blame (of course) & doubled down on the dialectic and critique, arguing reason itself was the culprit, mutating into domination. lol. This was how they externalized blame, never admitting the revolutionary spark they admired in Marx and Lukacs led directly to the very monsters they fled from. What a couple of assholes.

霍克海默和阿多諾知道他們處在一個兩難的境地,因為他們用理性來批評理性。阿多諾甚至承認他們用啟蒙自己的工具來譴責啟蒙的極權主義轉變的「表演性矛盾」。然而,他們認為沒有選擇;哲學本身必須成為自我批判的。在他們看來,從笛卡爾到康德,早期思想家將一個主權理性主體放在中心位置,即使是像盧梭或馬克思這樣的進步繼承人也無法阻止理性演變成支配。他們將馬克思的意識形態批判擴展到經濟之外,涵蓋了文化和意識的每個領域。與葛蘭西相對樂觀的文化霸權概念不同,阿多諾和霍克海默對無產階級(或任何人)能否抵抗這種新的全面系統持悲觀態度。這也是他們與盧卡奇對革命無產階級的信仰分道揚鑣的地方。

根據阿多諾,唯一的希望是「負面辯證法」。這意味著一種不滿足於虛假整體的無情批判。他們揭穿了電視觀眾的「虛假笑聲」,以及啟蒙對自由的承諾如何變成一個黑暗的笑話。矛盾是他們的特色。通過強調現代社會如何在聲稱理性同時創造新的神話(如消費主義),法蘭克福學派的創始人為幾代激進分子質疑從好萊塢大片到工具理性科學的一切鋪平了道路。總之,霍克海默和阿多諾是批判理論的開創者。他們的遺產是一種無情、無盡的批判方法。

我們應該花點時間來看看他們1950年的《專制人格研究》,以及其中的F-量表(F代表法西斯主義),這是他們試圖確定人們為何會落入極權主義陷阱的嘗試。因此,他們利用弗洛伊德的視角,探討了壓抑的慾望和社會順從如何培育法西斯傾向,這直接回應了納粹的恐怖。但他們避開了為什麼他們的心愛的辯證法(在這裡,否定之否定)最終落在法西斯主義,而不是共產主義上這個問題。而不是承認這點,他們將責任推卸給了理性本身,認為它是罪魁禍首,變成了支配。哈哈。這就是他們將責任推卸給外界的做法,從未承認他們所欽佩的馬克思和盧卡奇的革命火花直接導致了他們逃離的怪物。真是一對混蛋。

The Frankfurt School 2- Herbert Marcuse Pervert Druggy Boogaloo.

Herbert Marcuse was the Frankfurt School's rockstar, pervy uncle, swapping Horkheimer and Adorno's grim 1940s noir for a 1960s psychedelic rebellion vibe. He fused Hegelian dialectics, Marxian economics, and Freudian psychoanalysis into a volatile cocktail, and his eyes were on the revolution, not just critique. In One-Dimensional Man (1964), he famously called out advanced industrial society for its "comfortable, smooth, reasonable, democratic unfreedom." Capitalism, he said, is a tricky bastard: it stuffs us with gadgets and snacks, making us so cozy we don't even notice our chains. Forget Marx's gritty exploitation at the factory; Marcuse argued consumer culture sedates us, flattening dissent and imagination into a "one-dimensional" haze. It's the Matrix, but with Netflix, Amazon, & Door Dash.

Marcuse remixes Marx's false consciousness with Freud's psyche: the system doesn't need jackbooted stormtroopers when it's got our subconscious on lock. Borrowing Freud's superego, he argued we've internalized authority so deeply we police ourselves. So theres no need for a scowling Big Brother. The old-school patriarchs (mean dads, hellfire preachers) are gone; now, "all domination assumes the form of administration." Power wears a tie, not a jackboot. We think we're free because we've got 50 soda brands, but, for marcuse, the pervy revolutionary, 'real' freedom is to torch the system, and that's gone. So Marcuse is in Golden Age California, is basically screaming "Wake up, comrades!"

法蘭克福學派 2 - 赫伯特·馬庫塞 迷幻藥邪惡狂熱。

赫伯特·馬庫塞是法蘭克福學派的搖滾明星和色老頭,他拋棄了霍克海默和阿多諾沉悶的 1940 年代黑色電影,換上了 1960 年代迷幻的叛逆氣息。他將黑格爾的辯證法、馬克思的經濟學和弗洛伊德的精神分析融合成了一種易燃的雞尾酒,他的目光不僅僅是批評,而是革命。在《一維人》(1964 年)中,他著名地指責先進工業社會的「舒適、光滑、合理、民主的不自由」。他說,資本主義是一個狡猾的混蛋:它用小玩意和零食塞滿我們的肚子,讓我們感到如此舒適,以至於我們甚至沒有注意到自己的鎖鏈。忘記馬克思在工廠裡的艱苦剝削吧;馬庫塞認為,消費文化使我們鎮定,將異議和想像力壓平成一種「一維」的迷霧。這就是《黑客帝國》,但使用了 Netflix、Amazon 和 Door Dash。

馬庫塞將馬克思的虛假意識與弗洛伊德的心理混合:當它掌握了我們的潛意識時,系統就不需要穿著長靴的暴風雨士兵了。借鑒弗洛伊德的超我,他辯稱我們已經將權威內化得如此深刻,以至於我們自己都在監管自己。所以不需要一個皺著眉頭的大哥。老派的家長(嚴厲的爸爸、地獄火傳道者)已經不見了;現在,「所有統治都採取了行政的形式」。權力穿著領帶,而不是長靴。我們認為自己很自由,因為我們有 50 個汽水品牌,但對馬庫塞來說,這個色老頭革命者認為,真正的自由是燒毀這個系統,而這已經不復存在。所以馬庫塞在黃金時代的加州,基本上是在大喊「同志們,醒醒!」

Marcuses drive here digs in to the "negation of the negation" that Adorno and Horkheimer feared led to fascism or Stalinist ethno-socialism. For Hegel, the dialectic resolves contradictions into a higher unity; for Marx, it's the proletariat smashing capitalism. Marcuse, though, saw a fork: if the negation of bourgeois society leans on Freud's Thanatos (death-drive), it spirals into fascism-a violent, mythic return to ethnos, race, or "blood and soil." Marcuse called fascism a false negation, a counter-revolutionary scam that resolves capitalism's tensions through authoritarian spectacle, not emancipation. Think Nazi rallies or Stalin's Russian ethnos pivot post-Korenizatsiya, where universalism got swapped for nationalist purges - one Marcuse felt directly as a Jew in exile. Both, for Marcuse, were Thanatos-fueled dead-ends, aestheticizing politics to mask repression.

So, enter Eros, Marcuse's game-changer. In Eros and Civilization (1955), he flips Freud's grim view that civilization demands repression. Why not, he asks, use our advanced society to liberate instincts? Why not just wank and perv everyone in the West. His argument was Eros, the life-drive, play, polymorphous sexuality, can reroute the dialectic's energy away from fascist ethno-socialism toward a non-repressive utopia. Instead of resolving contradictions with mythic unity (race, nation), Eros fuels a "great refusal": rebellion via art, erotic freedom, and aesthetic imagination. It's not just economic revolt but a cultural, libidinal middle finger to capitalism's "performance principle" (all work, no play). Marcuse's vision? A society where labor and libido just mingle together at a mixer, not clash.

馬庫塞的觀點深入探討了阿多諾和霍克海默所恐懼的「否定之否定」現象,他們認為這導致了法西斯主義或史達林式的民族社會主義。對於黑格爾來說,辯證法解決了矛盾,達到更高的統一;對於馬克思來說,這是無產階級粉碎資本主義。然而,馬庫塞看到了一個分歧:如果對資產階級社會的否定依賴於弗洛伊德的死亡本能(Thanatos),它就會螺旋式地走向法西斯主義——一種暴力、神話般的回歸民族、種族或「血與土」。馬庫塞將法西斯主義稱為虛假的否定,一場反革命騙局,它通過威權的表演,而不是解放,來解決資本主義的緊張局勢。想想納粹集會或史達林在本土化(Korenizatsiya)後的俄羅斯民族轉變,普遍主義被民族主義清洗所取代——這正是馬庫塞作為一名流亡猶太人直接感受到的。對馬庫塞來說,這兩種情況都是由死亡本能驅動的死胡同,將政治美化為掩蓋壓迫。

因此,Eros的出現,成為馬庫塞的轉折點。在《愛與文明》(Eros and Civilization)(1955 年)中,他顛覆了弗洛伊德對文明需要壓抑的嚴峻觀點。他提出,為什麼不利用我們的先進社會來解放本能?為什麼不讓西方的每個人都享受性快感和變態行為。他的論點是,Eros,即生命本能、遊戲和多形態的性,可以重新導向辯證法的能量,遠離法西斯民族社會主義,朝著一個非壓抑的烏托邦前進。相反於用神話般的統一(種族、國家)來解決矛盾,Eros驅動了一種「偉大的拒絕」:通過藝術、性自由和審美想像進行叛逆。這不僅僅是經濟上的叛亂,而是對資本主義「表現原則」(只工作,不玩樂)的文化的、性慾的侮辱。馬庫塞的願景?一個勞動和性慾可以和諧共存,而不是衝突的社會。

He did have a bit of the earlier Frankfurt School's noir side. In One-Dimensional Man, he warned even liberal societies flirt with fascist tendencies, neutralizing contradictions through admin and fake freedom. His "Repressive Tolerance" (1965) an essay that many have covered said tolerance can be a con, absorbing dissent so nothing changes. True tolerance might mean shutting down oppressive ideas.

Unlike Adorno's mopey "reason's doomed" shtick, Marcuse saw revolutionary energy in the the margins of Western society - students, minorities, anti-colonial rebels, hippies, feminists, LGBTQ activists. The 1960s New Left went nuts over all of this wank, perv, drugs, marginalized people stuff, crowning him their "guru." So, Marcuse broadened Marx's revolution beyond class to include psychological, cultural, and sexual liberation. Where Adorno mourned the dialectic's fascist turn, Marcuse gave it drugs and a subscription to Hustler, insisting the 'revolution could work this time™" and negation could birth to the 'real revolution™,' not just ethno-socialist dictatorships.

他確實保留了一些早期法蘭克福學派黑色電影方面的元素。在《一維人》中,他警告即使是自由主義社會也會調情法西斯傾向,通過行政和假自由來中和矛盾。他在《壓抑的寬容》(1965 年)一文中(許多人都有討論這篇文章)指出,寬容可能是一種騙局,吸收異議以確保一切保持不變。真正的寬容可能意味著關閉壓迫性的想法。

與阿多諾沮喪的「理性註定失敗」的把戲不同,馬庫塞在西方社會的邊緣看到了革命能量——學生、少數族裔、反殖民叛軍、嬉皮士、女權主義者、LGBTQ 活動家。1960 年代的新左翼對所有這些性愛、變態、毒品和邊緣化群體的事物著迷,將他加冕為他們的「導師」。因此,馬庫塞將馬克思的革命擴大到階級之外,包括心理、文化性和性解放。當阿多諾為辯證法轉向法西斯主義而哀悼時,馬庫塞給它提供了毒品和《花花公子》雜誌訂閱,堅持「這次革命可以成功」和「真正的革命」可以誕生,而不僅僅是民族社會主義獨裁。

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre was French Existentialism's Galouise smoking, bohemian, Parisian enfant terrible of existentialism. He's the guy who quipped "Hell is other people" (We'll get to that below).

First, lets cover Sartre's key mantra, "existence precedes essence," which basically inverted traditional Philosophy. So, where old-school thinkers from Plato to Descartes to Kant assumed some fixed human nature or soul (an essence) that determines our existence, Sartre said Non! We simply exist, and it's up to us to create who we are through our actions. So, you're not born a hero or a coward, a "woman" or a "man" in any essential sense, you become one by what you do. This radical freedom was ripped off from Heidegger and Husserl's phenomenology (Sartre lifted these ideas on consciousness and being while drinking cocktails in 1930s Berlin, as ze legends have it). But Sartre gave it a twist: if there's no God and no fixed nature, we are "condemned to be free," wholly responsible for our choices. He even reimagined Descartes's Cogito so it was not as proof of a solid self, but as a fleeting, self-aware nothingness that must constantly define itself.

讓-保羅·薩特

讓-保羅·薩特是法國存在主義的標誌性人物,他是一個博學多才、充滿叛逆精神的巴黎人。他就是那個曾說過「地獄是別人」的人(我們稍後會討論這句話)。

首先,讓我們來探討薩特的關鍵口號:「存在先於本質」,這基本上顛覆了傳統哲學。因此,從柏拉圖到笛卡爾,再到康德,傳統的思想家都假設存在一個固定的人類本性或靈魂(本質),決定了我們的存在。但薩特卻說不!我們只是存在,並我們有責任透過自己的行動去創造(Pika:並定義?)我們是誰。所以,你天生不是英雄也不是懦夫,不是以任何本質意義上的「女性」或「男性」,你通過自己的行為成為那個人。這種激進的自由觀是從海德格和胡塞爾的現象學中借鑒而來的(據傳說,薩特在20世紀30年代的柏林喝雞尾酒時,從中汲取了這些關於意識和存在的想法)。但薩特給它帶來了新的視角:如果沒有上帝,沒有固定的本性,我們就被「注定要受自由之苦」,完全對自己的選擇負責。他甚至重新詮釋了笛卡爾的「我思故我在」,不是作為一個堅實的自我證明,而是一個虛無、自我意識的瞬間,必須不斷地定義自己。

In Being and Nothingness (1943), he paints human consciousness as an empty, negating force.. We are defined by what we are not, by the possibilities we chase. Super ze exeztentializm, no? 🍷 Sartre delivered it in an irreverent tone that really appealed to a generation finding its way out of the shadow of WWII.

He also addressed Hegel's master-slave dialectic in his own way. in the famous chapter on "The Look," Sartre described how finding someone else's gaze instantly turns you into an object (cue that awkward feeling of being caught spying through a keyhole). Unlike Hegel's version, in Sartre's world this struggle for recognition has no happy dialectical resolution. It's all an endless seesaw of people objectifying each other, a "hell" of intersubjectivity without resolution. (Fun fact-Marcuse quipped that this sounded like "adolescent paranoia." NGL, Sartre's early philosophy feels super edgelord about how other people always ruins your day.

在《存在與虛無》(1943)中,他將人類意識描繪成一個空洞、否定的力量。我們被我們所不是的東西、我們追求的可能性所定義。這就是極致的存在主義,對吧?🍷 薩特以一種不敬的語氣表達了這一點,這深深吸引了二戰陰影中尋找出路的這一代人。

他還以自己的方式探討了黑格爾的主奴辯證法。在著名的「目光」一章中,薩特描述當你發現別人的目光時,你瞬間就變成了一個客體(想想那種被抓到偷窺的尷尬感覺)。與黑格爾的版本不同,在薩特的世界中,這場爭取承認的鬥爭沒有快樂的辯證解決。這是一個沒有解決的、人們互相物化的無盡拉鋸戰,一個沒有解決的「地獄」的相互主體性。(有趣的是,馬庫塞開玩笑說這聽起來像「青少年的偏執狂」。老實說,薩特早期哲學的確讓人覺得其他人總是破壞你的一天,這有點像極端的邊緣人思維。

So anyway, edgelord Sartre made subjectivity and freedom the centerpiece of philosophy, boldly critiquing earlier notions of the subject. So, to Kant, for the whaddabout Kant people) the subject was a rational law-giver; to Marx, the human essence was shaped in social labor... then to Sartre, the subject was an ongoing project, a nothingness that must create meaning against absurd odds. For edgelord Sartre, this was an emancipatory move in its own right: it told people that no matter their circumstances, they have some freedom to reinvent themselves (albeit with existential dread lurking). Some took all this to mean that Sartre's existentialism was a banner for individual autonomy and authenticity; to live in "good faith" by embracing your freedom, rather than in "bad faith" by hiding behind excuses (be it God, biology, or "I was just following orders").

But Sartre wasn't just the poster boy for lonely existential angst. The philosophical shape-shifter, he dove headfirst into Marxism in the 1950s, pulling off one of history's most unlikely intellectual hookups: existentialism meets Marxism. In Search for a Method (1957) and the doorstop-sized Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), he argued individual freedom's cool and all, but it's useless if class, colonialism, and economic exploitation keep folks chained. Marxism, he declared, was the "unsurpassable horizon" of his time-history's backbone-but it had calcified into Soviet dogma. Sartre thought existentialism could spice it up by putting human agency and praxis back in the driver's seat.

所以,無論如何,薩特將主體性和自由置於哲學的中心,大膽地批評了先前對主體的觀念。因此,對康德來說,主體是一個理性的立法者;對馬克思來說,人類的本質是在社會勞動中形成的... 而對薩特來說,主體是一個持續的項目,是一個必須在荒謬的逆境中創造意義的虛無。對薩特來說,這本身就是一種解放性的舉動:它告訴人們,無論他們的處境如何,他們都有自由重新創造自己(儘管存在著潛在的存在的恐懼)。有些人認為這意味著薩特的存在主義是個人自主和真實性的旗幟;通過擁抱自由,以「善意」的方式生活,而不是以「惡意」的方式生活,隱藏在藉口背後(無論是上帝、生物學還是「我只是服從命令」)。

但薩特不僅僅是孤獨存在焦慮的象徵。這個哲學的變形者,他在20世紀50年代投入了馬克思主義,完成了歷史上最不可能的知識分子結合之一:存在主義遇見馬克思主義。在《方法的探索》(1957)和龐大的《辯證理由的批判》(1960)中,他認為個人的自由固然很棒,但如果階級、殖民主義和經濟剝削讓人們保持被鎖鏈束縛,那就一文不值。薩特宣佈,馬克思主義是他時代「不可超越的視野」——歷史的脊樑,但它已經變成蘇聯的教條。薩特認為,存在主義可以通過將人類的代理和實踐重新放在駕駛座上,為它增添一些活力。

Here's where Sartre channels Moses Hess, the OG of using socialism to summon a collective consciousness and flipped Descartes's "I think, therefore I am" into "We do, therefore we are." Like Hess, Sartre saw humanity's essence as something we forge together through action, not some pre-baked soul. But, while Hess later leaned into ethnos (think his Jewish nationalist turn in Rome and Jerusalem), Sartre kept it universal, eyeing a collective consciousness aimed at a teleological prize: a society free from alienation and scarcity. In Critique, he reworks Hegel's dialectic and Marx's materialism, arguing that through praxis (think workers uniting or rebels storming barricades) we raise a collective essence, a shared project to smash oppressive structures and build a liberated world.

This is Sartre's spin on the negation of the negation, a nod to the Frankfurt School's dialectic. Unlike Marcuse's Eros vs. Thanatos face-off, Sartre sees collective praxis as negating capitalism or colonialism to birth a new social reality. So not fascist ethno-socialism, but a humanist horizon. His "group-in-fusion" concept, like a mob seizing the Bastille, shows individuals melting into a collective subject, their consciousness raised toward a shared telos: concrete freedom, where everyone's potential shines. It's Marx's class consciousness with an existentialist glow, freely chosen, yet shaped by gritty material conditions.

在這裡,薩特汲取了摩西·赫斯的思想,赫斯是利用社會主義召喚集體意識的開創者,他將笛卡爾的「我思故我在」轉變為「我們做故我們在」。像赫斯一樣,薩特認為人類的本質是我們通過行動共同鍛造的,而不是預先烘焙的靈魂。但與赫斯不同,薩特保持了普遍性,他眼中的集體意識旨在追求一個終極目標:一個擺脫異化和匱乏的社會。在《批判》中,他重新構建了黑格爾的辯證法和馬克思的物質主義,認為通過實踐(想像工人團結或叛軍衝擊路障),我們建立起集體的本質,一個共同的項目,以粉碎壓迫的結構並建立一個解放的世界。

這是薩特對否定之否定的演繹,對法蘭克福學派的辯證法的點頭。與馬庫塞的愛欲與死亡之爭不同,薩特認為集體的實踐是否定資本主義或殖民主義,以誕生一個新的社會現實。所以不是法西斯民族社會主義,而是一個人文主義的視野。他的「融合群體」概念,就像一群人奪取巴士底獄一樣,展示了個人融為一體的主體,他們的意識提升到一個共同的終極目標:具體的自由,每個人都能夠發揮自己的潛能。這就是帶有存在主義光環的馬克思的階級意識,自由選擇,但由艱苦的物質條件塑造。

Sartre the edgelord rips into "orthodox" Marxists for turning people into history's puppets and bourgeois existentialists for navel-gazing past economics. His synthesis? History's a messy dance of human projects under conditions we don't pick (man making history). He tosses in the "practico-inert," where our actions harden into institutions that bite us back. Think about Marx's reification with a Sartrean smirk. A worker's revolt, for instance, is both a free leap and a spark from economic misery. This puts Sartre in the same millieu as Gramsci and Lukacs, keeping revolution's fire but hyping agency and culture.

So the edgelord who started off saying "Hell is other people" ended up marching with them, backing Algeria's anti-colonial fight, Vietnam's rebels, and Paris '68 protesters. Mr. Individualist found his place summoning the collective consciousness of the marginalized, editing radical journals and snubbing the 1964 Nobel Prize.

Not only did he think the West needed to lose its collective consciousness, he basically thought it needed to cuck itself to the third world. In the preface to Frantz Fanon's "Wreched of the Earth, Sartre said "For in the first days of the revolt you must kill: to shoot down a European is to kill two birds with one stone, to destroy an oppressor and the man he oppresses at the same time: there remain a dead man, and a free man; the survivor, for the first time, feels a national soil under his foot." He really wrote that. What a cucky edgelord.

薩特這個邊緣人批評了「正統」的馬克思主義者,認為他們把人們變成歷史的木偶,也批評了資產階級存在主義者,認為他們只關注自己的內心,忽視了經濟問題。他的綜合觀點是,歷史是一場混亂的人類項目的舞蹈,在我們無法選擇的條件下進行(人類創造歷史)。他引入了「實踐-慣性」的概念,我們的行動固化為機構,反過來咬我們一口。想像一下,帶著薩特的微笑,馬克思的商品化。例如,工人的起義,既是一個自由的跳躍,也是經濟困境的火花。這讓薩特處於與葛蘭西和盧卡奇相同的環境中,他保留了革命的火種,但強調了能動性(agency)和文化。

所以,這個開始說「地獄是別人」的邊緣人,最終與他們一起遊行,支持阿爾及利亞的反殖民鬥爭、越南的叛軍和1968年巴黎的抗議者。這個個人主義者發現自己的位置在於召喚被邊緣化的集體意識,編輯激進的期刊,並拒絕1964年的諾貝爾獎。

他不僅認為西方需要失去集體意識,他基本上認為西方需要向第三世界屈服。在《地球上的受苦者》的序言中,薩特說:「因為在起義的最初幾天,你必須殺死:射殺一個歐洲人就是一石二鳥,同時摧毀了一個壓迫者和他壓迫的人:剩下一個死人,一個自由的人;倖存者第一次感到腳下有一片國家的土地。」他真的寫了這句話。真是一個屈服的邊緣人。

Simone de Beauvoir: From Other to Collective Awakening, and she's also a Perv.

She was Sartre's lifelong partner in crime though history often played her down as Sartre's sidekick.

Fun fact - Beauvoir didn't start out waving a feminist flag. When The Second Sex dropped in 1949, she caught flak and swore she wasn't an activist...yet. She was a philosopher first, sparring with Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and Camus on freedom and existence, only to have her "women's stuff" dismissed, which probably drove some of her work.

Beauvoir's magnum opus The Second Sex (1949) basically invented feminist existentialism and jump-started second-wave feminism. Her most famous assertion, "One is not born, but becomes a woman," is a choice line that reframes Sartre's existential creed ("existence precedes essence") in feminist terms. By this, she meant that "woman" is not a natural or eternal fact but a situation, here, a social construct imposed on females. Women throughout history, Beauvoir argued, have been defined as 'the Other,' or, the second sex, in relation to man who proclaims himself the One (the default, the essential human). Here, she deploys Hegel's oh so popular master-slave dialectic: just as Hegel described how one consciousness tries to dominate another, Beauvoir shows how men have made women their mirror, their subordinate, to affirm their own self-conception. But crucial twist unlike Hegel's slave who can eventually rebel and invert the relation, women's oppression had some unique sticky features. Beauvoir, reading Hegel via Alexandre Kojeve's lectures, noted that men universalized themselves as essential and labeled women as inherently "inferior," using every supposed "feminine" weakness as proof of women's second-class status. Her take was society set up a game women couldn't win: if they're passive, they're inferior by nature; if they're ambitious or smart, they're unnatural.

西蒙·德·波伏娃:從他者到集體覺醒,她也是個色鬼。

她一生都是薩特的犯罪夥伴,儘管歷史經常把她描述為薩特的副手。有趣的是,波伏娃最初並不是揮舞女權旗幟的人。當《第二性》(1949)出版時,她受到批評,並發誓自己不是活動家... 但她確實是。她首先是一個哲學家,與薩特、莫里斯·梅洛-龐蒂和卡繆就自由和存在進行辯論,但她的「女性問題」被忽視,這可能促使她寫了這本書。

波伏娃的巨著《第二性》(1949)基本上創造了女權存在主義,並啟動了第二波女權主義。她最著名的主張,「人不是生來就是女人,而是成為女人」,重新詮釋了薩特的存在主義信條(「存在先於本質」)的女權主義觀點。她所說的,不是「女人」是一個自然或永恆的事實,而是一種情況,一個社會對女性施加的結構。波伏娃認為,歷史上,女性被定義為「他者」,即第二性,與自稱是「一」(預設的、本質的人類)的男性相對。這裡,她運用了黑格爾非常受歡迎的主奴辯證法:正如黑格爾描述了一個意識試圖支配另一個意識,波伏娃展示了男性如何讓女性成為他們的鏡子,他們的下屬,以肯定他們自己的自我概念。但關鍵的轉折是,與黑格爾的奴隸不同,最終可以叛逆並反轉關係,女性的壓迫具有獨特的粘性特徵。波伏娃在閱讀亞歷山大·科傑夫對黑格爾的講座時指出,男性將自己普遍化為本質,並標記女性為「低等」的,使用每一種所謂的「女性」弱點來證明女性的低等地位。她的觀點是,社會設置了一個女性無法贏的遊戲:如果她們被動,她們是天生低等的;如果她們有抱負或聰明,她們是不自然的。

Beauvoir's big question: can women forge a collective consciousness to break free from this prison? Unlike Sartre's "group-in-fusion" charging toward a classless utopia, Women lack the concrete avenues for solidarity that oppressed classes have- no separate homeland, no unified culture, being dispersed among their male family units- so they couldn't just stage a proletarian-style revolt. As Beauvoir observes, women are "the Other" in a situation where they cannot fully break free: they are taught to identify with men (father, husband, etc.) rather than with other women as a group. In Hegelian terms, the Master (man) keeps the slave (woman) so embedded in his world that she can't form an independent für-sich (for-itself) consciousness to overthrow him. In other words, patriarchy's trick is tying women to men (dads, husbands) over sisterhood, stunting the collective essence Sartre saw in revolutionary mobs. So here she fuses Hegel, Marx, and Freud (she even discusses how women internalize their condition via upbringing and psychology) into a new, liberatory theory of gender. Beauvoir, channeling "We do, therefore we are," insisted women could awaken through praxis, acting against their "Other" status to claim subjecthood. She showed how patriarchal society constructed femininity as a kind of prison- gilded for some, brutal for others- and how myths from Aristotle and Rousseau to cinema, etc., perpetuated the idea that woman's "essence" is to be man's complement (or opposite).

波伏娃的大問題是:女性能否鍛造集體意識,從這個監獄中解放出來?與薩特的「融合群體」向著無階級烏托邦衝刺不同,女性缺乏與壓迫階級相同的具體團結途徑——沒有獨立的祖國,沒有統一的文化,她們分散在男性家庭單位中——所以她們不能簡單地進行無產階級式的叛亂。正如波伏娃所觀察到的,女性是「他者」在一個她們無法完全擺脫的境地:她們被教導與男性(父親、丈夫等)認同,而不是與女性群體認同。用黑格爾的術語來說,主人(男性)讓奴隸(女性)深深地融入他的世界,以至於她們無法形成獨立的「為自己」的意識,以推翻他。換句話說,父權制的詭計是將女性與男性(父親、丈夫)聯繫起來,而不是與姐妹情誼,這阻礙了薩特在革命群體中看到的集體本質。所以在這裡,她融合了黑格爾、馬克思和弗洛伊德(她甚至討論了女性如何通過教育和心理學內部化她們的處境)形成一個新的、解放的性別理論。波伏娃堅持女性可以通過實踐覺醒,行動起來,反對她們的「他者」地位,以主張主體性。她展示了父權社會如何將女性性建構成一種監獄——對一些人來說是金碧輝煌的,對另一些人來說是殘酷的——以及亞里士多德、盧梭到電影等神話如何延續了女性「本質」是成為男性補充(或相反)的想法。

She opened a huge door with her sex-gender split: being female (sex) isn't being "woman," a line that birthed modern gender theory and, to the chagrin of radfems, queer theory. Beauvoir owned the messy contradictions: women can be complicit, chasing marriage's safety like Marx's false consciousness.

She challenged Descartes' "I think, therefore I am" by effectively asking, who gets to say "I"? She also called out Marx and Engels for shrinking women's woes to economics, insisting their existence (biological, social, psychological) demands a broader lens, prefiguring intersectional thinking. Freud also got a half-nod for how women internalize passivity through upbringing, but she wasn't here for his reductive psychobabble garbage.

She engaged the collective consciousness she was raising and actively guided its praxis & telos. By the 1970s, she went all-in, backing France's feminist movement and the 1971 abortion rights Manifesto of the 343, showing the power of collective action. She also opened the door for later thinkers like Betty Friedan, Audre Lorde, Judith Butler, and basically any who would further explore how society 'others' people by gender, race, etc., stand on her work, really, TBH.

So, more fun facts, Beauvoir’s “freedom” got her canned from teaching in 1943 for allegedly seducing a 17-year-old student, among others, with claims she and Sartre groomed young women for affairs. Worse, she signed a 1977 petition backing the decriminalization of some adult-minor relations. Did anyone really expect anything less? Lol.

她通過性-性別(sex-gender)的區分打開了一扇巨大的門:成為女性(sex)並不意味著成為「女人」,這句話孕育了現代性別理論,後來也讓激進女權主義者感到沮喪,孕育了酷兒理論。波伏娃承認了這些混亂的矛盾:女性可能是同謀,追求婚姻的安全,就像馬克思的虛假意識。

她挑戰了笛卡爾的「我思故我在」,有效地問道,誰有權說「我」?她還批評了馬克思和恩格斯,將女性的問題簡化為經濟問題,堅持她們的存在(生物、社會、心理)需要更廣泛的視角,預示了交織性思考(intersectional thinking)。弗洛伊德也得到了半個點頭,因為他解釋了女性如何通過教育內部化被動,但她不接受他的簡化心理廢話。

她參與了她所喚醒的集體意識,並積極指導其實踐和終極目標。到20世紀70年代,她全力支持法國的女權主義運動,並支持1971年《343人宣言》,這是一份支持墮胎權的宣言,展示了集體行動的力量。她還為後來的思想家如貝蒂·弗里丹、奧德麗·洛德、朱迪斯·巴特勒,以及任何進一步探索社會如何通過性別、種族等「他者」人們的思想打開了大門。

所以,更多有趣的事實,波伏娃的「自由」在1943年讓她失去了教學工作,據稱她誘惑了17歲的學生,並有說法她和薩特培養年輕女性與他們發生婚外情。更糟糕的是,她簽署了1977年支持部分成年人與未成年人關係非刑事化的請願書。有人真的期待她有不同的行為嗎?哈哈。

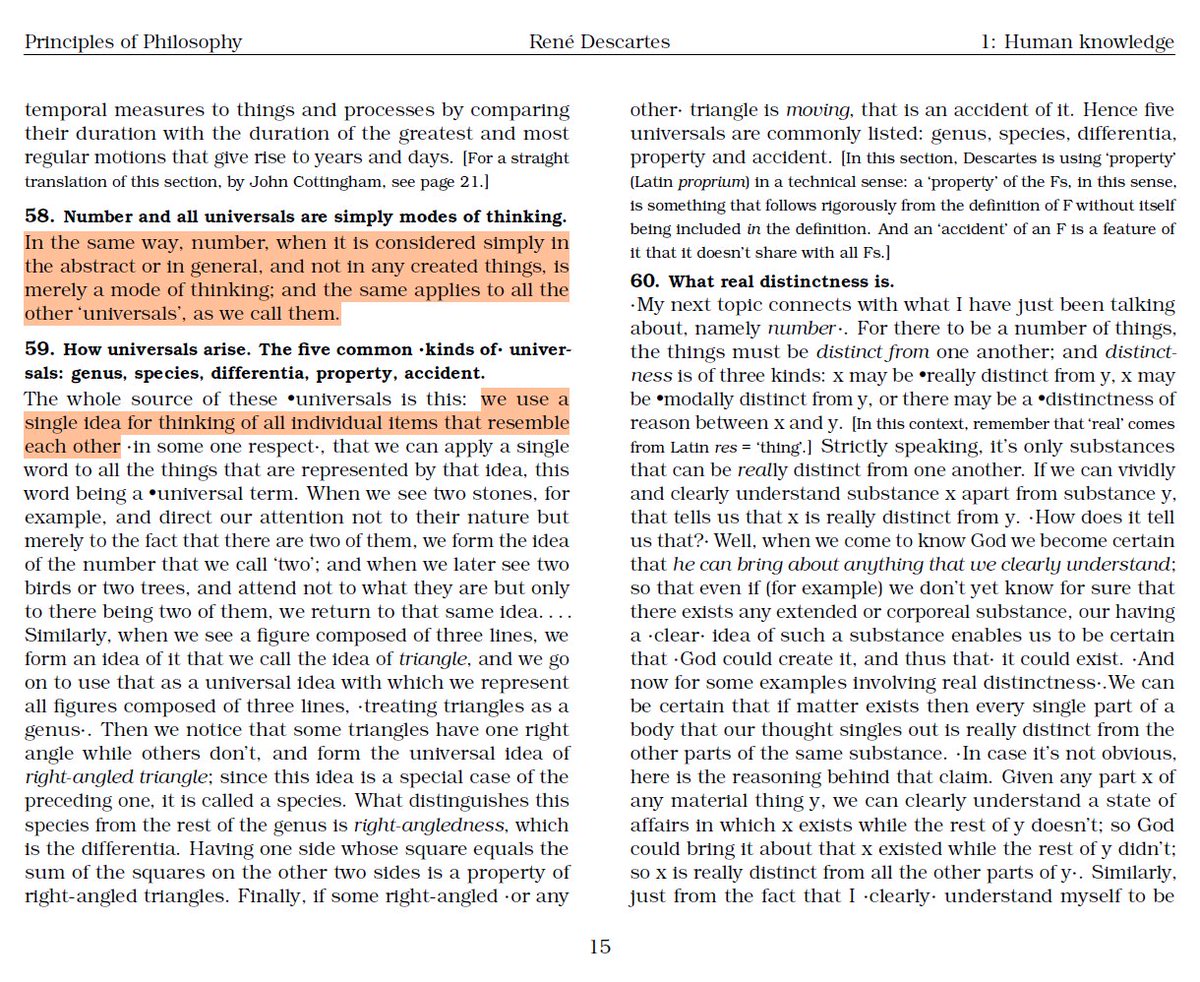

Descartes' philosophy aligned with nominalism on key points, thereby reinforcing nominalist tendencies in modern thought. In his Principles of Philosophy (1644), Descartes explicitly writes that "number, when considered simply in the abstract or in general, and not in any created things, is merely a mode of thinking; and the same applies to all the other universals". He explains that universals arise because we use "a single idea for thinking of all individual items which resemble each other," applying a common term to them. In other words, for Descartes a "universal" is just a mental label we apply to many similar particulars. It exists in our thought rather than as a real entity outside the mind. Descartes here claim universals are merely 'modes of thinking,' implying they have no mind-independent reality at all. This is essentially a classic nominalist position.

By rejecting the existence of any extramental universals or forms, Descartes broke with the older Scholastic realism (which held that universals are real). Instead, he inclined toward the view that only individual substances and their particular properties are real - universals are just concepts. Overall, Descartes' ontology is "nominalist-inclining." This means that while he may not use the term "nominalism," his approach to universals is in line with nominalist thinking.

笛卡爾的哲學在關鍵點上與唯名論一致,從而加強了現代思想中的名目論傾向。在他《哲學原理》(1644)中,笛卡爾明確寫道:「當我們僅僅從抽象或一般角度考慮數字,而不考慮任何創造物時,它只是思維的一種方式;其他所有普遍概念也是如此。」他解釋說,普遍概念的產生是因為我們使用「一個概念來思考所有相似的事物」,並對它們應用一個共同的術語。換句話說,對笛卡爾來說,一個「普遍概念」只是我們對許多相似的特定事物應用的心理標籤。它存在於我們的思想中,而不是作為心外實在的實體。笛卡爾在這裡聲稱普遍概念只是「思維的方式」,這意味著它們完全沒有獨立於心智的現實。這基本上是一個經典的唯名論立場。

通過拒絕任何心外普遍概念或形式的存在,笛卡爾與較早的學派現實主義分道揚鑣(學派現實主義認為普遍概念是真實的)。相反,他傾向於認為只有個別物質及其特定性質是真實的——普遍概念只是概念。總體而言,笛卡爾的存在論是「傾向唯名論的」。這意味著雖然他可能沒有使用「唯名論」這個術語,但他的普遍概念方法與唯名論的思考方式一致。

Descartes' nominalist-friendly stance influenced other early modern philosophers and the general intellectual climate. For example, his contemporary Thomas Hobbes took an explicitly nominalist position in Leviathan, writing that "there being nothing in the world universal but names; for the things named are every one of them individual and singular." Hobbes argues that a universal is just a name we impose on many individual things that resemble each other in some way. We see here a continuation of the same idea Descartes voiced - universals are human naming conventions, not independent realities. Hobbes and other 17th-century thinkers were part of the broader shift away from the medieval realist view of universals. Descartes was a central figure of this shift (often called the father of modern philosophy), so his adoption of a nominalist-like view helped normalize it in modern philosophy.

Really, Descartes carried forward the nominalist tradition by denying that universals have any existence apart from our thinking. While he did not originate nominalism, his philosophical framework - especially his Principles – clearly exemplifies nominalist principles and thus influenced subsequent thinkers to view universals as "just names."

笛卡爾對唯名論友好的立場影響了其他早期現代哲學家和一般的知識分子氣候。例如,他的同時代人托馬斯·霍布斯在《利維坦》中採取了明確的名目論立場,寫道:「世界上沒有什麼是普遍的,除了名字;被命名的事物都是各自的、獨特的。」霍布斯認為,一個普遍概念只是我們強加給許多相似個體的名稱。我們在這裡看到的是一樣的想法,笛卡爾之前表達過——普遍概念是人類的命名慣例,而不是獨立的現實。霍布斯和其他17世紀的思想家是從中世紀現實主義普遍概念觀念的更廣泛轉變的一部分。笛卡爾是這個轉變的關鍵人物(經常被稱為現代哲學的父親),所以他採用類似唯名論的觀點有助於在現代哲學中正常化這種觀點。

實際上,笛卡爾通過否認普遍概念在我們思考之外有任何存在,延續了唯名論傳統。雖然他沒有創造唯名論,但他的哲學框架,尤其是《原則》,明顯體現了唯名論原則,因此影響了後來的思想家將普遍概念視為「只是名稱」。

However, the concern about nominalism is usually about its wider implications. In other words, beyond the technical debate over universals. If nominalism becomes the prevailing mindset, it carries certain consequences for how we understand truth, reason, and society.

Nominalism denies that there are real universal essences (like "Justice," "Human Nature," or "Goodness") out there to be discovered. If only individual, particular things exist, then any general values or truths exist only as human conventions. This can lead to a form of relativism or skepticism about universal truth. (In fact, Weaver famously argued that the triumph of nominalism in the late Middle Ages was a pivotal turning point that eventually led to modern relativism). The idea is that once people no longer believe in universal truths or natures, society begins to lose its moorings.

然而,對唯名論的擔憂通常在於其更廣泛的影響。換句話說,超越了關於普遍概念的技術辯論。如果唯名論成為占主導地位的思維方式,它會對我們理解真理、理性和社會帶來一定後果。

唯名論否認存在真實的普遍本質(如「正義」、「人類本性」或「善良」)等待被發現。如果只有個別的、特定的事物存在,那麼任何普遍的價值觀或真理只存在於人類的慣例中。這可能會導致一種相對主義或對普遍真理的懷疑。事實上,韋弗著名地認為,中世紀後期唯名論的勝利是關鍵的轉折點,最終導致了現代相對主義。這個想法是,一旦人們不再相信普遍真理或本性,社會就會開始失去其錨定點。

Another issue is that that nominalism introduces a divide between the words we use and any deeper reality. If our terms are merely names we assign for convenience, then language no longer reveals the true nature of things. If nominalism is correct, our language and concepts might never get at any underlying truth – because there is no underlying universal truth, just isolated facts. This breeds a kind of intellectual superficiality or distrust in reason.

Perhaps the biggest issue critics highlight is that nominalism, especially when combined with Descartes' philosophy, paved the way for what philosophers like Max Horkheimer call "subjective reason." Without objective universals or inherent purposes in things, reason gets redefined as merely an instrument to serve subjective goals, rather than a means to grasp objective truths. Descartes himself, after denying universals, also dismissed the idea that things have inherent final causes or purposes we can know (he famously "ditched" Aristotle's final causes). One consequence is that the world is seen as raw material for human use. So we decide what purpose or meaning to assign to things, rather than discovering an intrinsic meaning. Put another way, imagine if a thing was created and it was unknowable to our minds, then it would have built-in purpose or telos. It is simply available as raw material for us to do whatever we want with it. In this framing, reality has no objective meaning in itself; it only has a subjective reality; the value exists only in our minds. This is basically a shift to a utilitarian and individualistic mindset: without objective ideals or ends, people tend to focus on their own will and utility. Horkheimer would later critique this as "instrumental" or purely means-ends reasoning.

另一個問題是,唯名論在我們使用的詞語和任何更深層次的現實之間引入了分歧。如果我們的術語只是我們為方便而分配的名稱,那麼語言不再揭示事物的真正本質。如果唯名論是正確的,我們的語言和概念可能永遠無法揭示任何根本的真理——因為沒有根本的普遍真理,只有孤立的事實。這會滋生一種知識上的表淺或對理性的不信任。

也許批評家們強調的最大問題是,唯名論,尤其是與笛卡爾的哲學相結合,為像馬克思·霍克海默(Max Horkheimer)所說的「主觀理性」鋪平了道路。沒有客觀的普遍概念或事物固有的目的,理性被重新定義為僅僅是服務於主觀目標的工具,而不是掌握客觀真理的手段。笛卡爾本人,在否認普遍概念後,也拒絕了事物具有我們可以知道的固有的最終原因或目的的想法(他著名地「拋棄」了亞里士多德的最終原因)。一個後果是,世界被視為人類使用的原材料。所以我們決定賦予事物什麼目的或意義,而不是發現內在的意義。換句話說,想像一下,如果一個事物被創造出來,而它對我們的頭腦是不可知的,那麼它就會有內在的目的或終極目標。它只是作為原材料提供給我們,讓我們隨意使用。在這種框架中,現實本身沒有客觀的意義;它只有主觀的現實;價值只存在於我們的頭腦中。這基本上是一種實用主義和個人主義的思維方式:沒有客觀的理想或終極目標,人們傾向於關注自己的意志和功利。霍克海默後來批評這是一種「工具性」或純粹的手段-目的推理。

So, nominalism is the issue because it undercuts the foundation for shared, objective meaning. It moves philosophy away from asking why or to what end (since it denies any real universals or purposes) and leaves only the question of how - how to manipulate particulars. This worry isnt just speculative. historically, modern philosophy and science were influenced by nominalism in ways that encouraged focusing on calculation and utility. Frankly, even a scientifically-minded nominalist like Hobbes ends up reducing truth to mere word-use and logic. Frankly, nominalism had a negative social impact. It's rightly blamed for reducing reason to utility, and eroding the belief in objective truth.

所以,唯名論成為問題,因為它削弱了共享、客觀意義的基礎。它讓哲學遠離了為什麼或為了什麼(因為它否認任何真實的普遍概念或目的),只剩下如何——如何操縱特定事物。這個擔憂並不是純粹的猜測。歷史上,現代哲學和科學受到唯名論的影響,以鼓勵關注計算和功利為方式。坦率地說,即使是科學頭腦的名目論者如霍布斯,最終也將真理簡化為僅僅是詞語使用和邏輯。坦率地說,唯名論對社會產生了負面影響。它合理地被歸咎於將理性減變為功利,並侵蝕了客觀真理的信念。