draft《Terms of Endearment 》(1983)

All Rights Reserved© 2025 Jules Vela

這部電影的中文名再次讓我感到震驚,因為它被翻譯成了《母女情深》。但實際上,這部電影講述的並不僅僅是母女關係,而是關於「親密關係」本身。那麼,為什麼要刻意把男性冷漠、自私、無法經營親密關係的問題,轉移並收窄為一個母女關係的敘事呢?因為這樣的主題不會冒犯父權——母女情是一個安全、溫順、去政治化的敘事。一個男性的自私,卻忙壞了一整群女人。

這部電影從來討論的就不只是母女關係,而是女性將自己的生命、身體與未來投注在錯誤的親密關係中,所付出的系統性代價。艾瑪與她的母親奧羅拉之間,確實存在控制、衝突、專制與權力不對等;但同時,那是一種真實存在的、持續行動的、在危機時刻不會消失的愛。與此形成殘酷對照的,是艾瑪的婚姻——那段被稱為「愛」的關係,在她一生最脆弱、最需要支持的時刻,卻全面缺席。

無論是東亞男性,還是美國白人男性,他們都極其擅長依靠父權與社會制度的庇護,輕而易舉地表演「愛」。只要長著一根男性生殖器,只要射出一些精液,他們就可以成為丈夫、成為父親,卻無需承擔任何與親密關係相匹配的責任。

艾瑪的丈夫是否愛她?如果我們仍然使用父權定義的「愛」——不打人、不離婚、偶爾回家——那他或許算是「合格」。但如果愛意味著責任、共擔、照護、情感回應與風險承擔,那麼答案是否定的。這個男人傑克敏感、自我、情緒化、逃避責任,並且始終把人生的風險轉嫁給艾瑪。他對家庭的所有幻想,實質上都是對免費女性勞動與無條件情緒供應的幻想。艾瑪拒絕母親的分手建議,不是因為她愚蠢,而是因為整個社會都在告訴她:「只要你選對男人、經營好家庭、養好孩子,你就會獲得幸福。」這不是個人錯誤,而是結構性的洗腦。

雖然這是一部1983年的電影,但在2025年,電影中的丈夫卻在「東亞式的男性無罪」敘事中,再一次被洗白。今天當人們不再討論男性責任,而是由男性視角來解說這部電影時,男性的罪惡被處理得如此輕描淡寫。即便如此,我仍然想談談這部電影帶給我的感受。

在這部電影裡,我看到的是女性與女性之間的關切與互助,也看到了1983年的美國白人男性,與當代東亞男性在結構與行為上的高度相似。女主角艾瑪與她的母親奧羅拉之間,雖然夾雜著控制、專制與權力不對等,但你無法否認奧羅拉對女兒的愛是真實存在的。那麼,劇中的丈夫呢?他對艾瑪是愛嗎?他隨心所欲、敏感、自我、自私,且顯得愚蠢。正是因為對愛情與婚姻的想像,對「擁有一個自己的家」的想像,艾瑪才毫不猶豫地拒絕了奧羅拉的分手建議,選擇了傑克這個男人,作為她未來想像中「家」的合夥人。這部電影如此清晰、直白地展示了女性盲目進入婚姻的可怖後果。作為女性的艾瑪,愉快地按下了啟動她死亡倒計時的時鐘。這種反覆為男性行為去責任化的敘事,本質上是一種男性免責權,這部電影展示的不是女性的盲目,而是在單一路徑敘事下,女性被系統性地引導進入一條不可逆的生命選項。

當時的父權制給了艾瑪這樣的承諾:如果你找到一個男人認真經營你和他的家,你就會收穫幸福,收穫愛。有了他好好地養育你的孩子,你就能收穫「幸福家庭」!但真相是什麼呢?真相是:當女人進入了一段不可撤銷的婚姻關係,這段婚姻關係帶來如此之多的不可撤銷的沉沒成本,真的會不可撤銷地驅趕女人走向死亡。

艾瑪天真、堅強。她生了三個孩子,獨自面對生活中的種種困難和困境。而她選擇的那個男人,總是冷漠而任性,在她所謂的家裡製造了現在和未來各種導致她死亡的困難。

婚姻的「沉沒成本」如何把女性推向疾病與死亡?現代醫學早已指出,長期情緒壓抑、無力感與慢性壓力,與多種女性高發疾病高度相關,包括但不限於:乳腺結節、乳腺癌、卵巢癌、免疫系統失調、心血管疾病。艾瑪的人生正是一個標準樣本。她的忍耐沒有改變婚姻,只是轉化成了她身體裡的惡性腫瘤。她承擔了三個孩子、長期貧困、丈夫的背叛與情感忽視。而這些並不是「不幸事件」,而是婚姻結構的正常運作結果。法律不會審判「把女人氣死」的男人,醫療系統只會記錄腫瘤,不會記錄壓迫。對女性而言,婚姻的沉沒成本不僅是金錢與時間,更是身體、健康與社會退出權。

艾瑪的忍耐並沒有改變她的生活,她婚後所遭遇的一切困難都來自於這個男人。然而,當時的父權制讓她相信,只要她順從而忍耐,就一定能夠迎來幸福。於是,哪怕最終她看到這個男人的出軌,看到這個男人對她的冷漠,聽到這個男人說對她沒有感情,這個男人欺騙她是為了調職,實際是為了另一個女人,讓她跟隨者一起搬家,她仍然在她死亡的那一刻釋懷了這個男人的背叛。最近有很多華人的女性,也看到了這部影片。大家在這部影片上看到了當下的自己。彈幕上大家都在咒罵艾瑪,認為她活該,指責她自己選擇了這個男人,選擇了生下三個孩子,並且還說他最後表達對兒子的愛,所以不值得可憐。我也不太能夠接受她最後並沒有看到真相。沒有看到真相,就這麼淒慘地死去的女人,是父權制的常態。

多麼恐怖啊,父權制的謊言讓她死亡,卻仍在愛著這個男人。哪怕在她的生命中,每一次遇到危險,幫她處理種種問題的都是她的母親、她自己和她的閨蜜,但她卻把自己所有的美好都交給了這個男人,而把所有的韌性和真實的自我都交給了她的閨蜜和她的母親。她的丈夫在聽到她得了惡性腫瘤的時候是那麼的淡然,甚至你可以感覺到他鬆了一口氣,內心有一種無法抑制的愉悅和被神眷顧的即將與出軌的女性結婚的輕鬆。彈幕上討論最多的還是他的大兒子。女人們都震驚強調著劣質基因的可怕,強調不要亂生孩子,父親的劣質基因是可以完美地遺傳給兒子,父親對妻子的冷漠和虐待也可以完整地遺傳給兒子。所謂「劣質基因」的恐慌,本質上是對父權行為模式代際複製的直覺恐懼。杰克可以在妻子即將死亡的那一晚,淡然、平靜地睡得像個死豬一樣,因為他能夠看到未來的光明和美好。一直痛恨杰克的母親奧羅拉,卻在女兒死後,趴在杰克的胸前哭泣,讓我感到無比的諷刺。當時醫學的不夠發達,讓她不能看到害死女兒的到底是誰。有些制度,從一開始就沒有打算讓女人活著走出來。有些男性可以「殺妻不見血」而收穫同情。

婚姻制度讓女性承擔絕大部分家務、育兒、情感勞動與危機管理,而男性往往儘享成果。研究顯示,婚姻品質與慢性壓力(stress overload)之間存在明顯關聯,而壓力負荷可部分解釋婚姻與健康差異;這意味著長期情緒與心理負擔對身體健康有實質影響。

整部電影中,是女性在照顧女性,是艾瑪的閨蜜與母親在主動照顧孩子與她,而男人享受結果。丈夫在得知她罹患惡性腫瘤時的冷靜與釋然令人作嘔。他沒有恐慌,沒有崩潰,沒有失眠。對他而言,未來反而更輕盈。奧羅拉在女兒死後伏在這個男人的胸前哭泣。

那是父權最成功的地方——即使母親親眼見證女兒被婚姻殺死,她仍然被訓練去安慰那個受益者,甚至把自己對女兒的愛投射在這個男人身上,認定他會後悔、會難過,而不過於苛責他。實際上,這個男人只會感到高興,因為艾瑪死在了「該死的時候」。

大量醫學研究指出,慢性心理壓力與身體疾病之間存在顯著關聯,尤其是在乳腺癌風險方面。慢性壓力會造成神經內分泌系統與免疫系統功能失調,進而促進腫瘤細胞的發生與演進。最新研究表明,慢性心理壓力與乳腺癌的發展存在生物學機制連結,這些壓力通過神經遞質的釋放和內分泌調節影響腫瘤形成與預後。

具體來說,研究發現慢性壓力可導致細胞、分子與神經迴路功能失調,促進乳腺癌的發生。壓力相關的焦慮與抑鬱等負面情緒在乳腺癌患者中尤為常見,而慢性壓力是這些精神負擔的重要危險因素之一。

在艾瑪罹患惡性腫瘤、命不久矣的時候,她的閨蜜想讓她開心,帶她去見了以前的朋友。選擇墮胎、選擇離婚的女性依然是光鮮亮麗的存在。唯獨那個一直忍耐、一直堅持、一直對丈夫出軌的婚姻仍抱有幻想的她,企圖用更多孩子捆綁婚姻關係;生了三個孩子的她卻得了惡性腫瘤。這種對「忍耐就會有回報」的結構性幻想,是父權文化對女性的心理綁架。

她罹病後照顧她、關心她、幫她照顧孩子的仍然是女性——她的母親和她的閨蜜。不管是艾瑪跟著杰克去到另一個城市,還是艾瑪因婚後一地雞毛、貧窮與「母職懲罰」深陷困境,以及在明知沒有錢的情況下仍懷了第三個孩子,所有家庭中的一切仿佛與這個男人無關。他只需專注於享受自己的生活、追求自我。他甚至可以通過羞辱、指責、強迫來逼迫她按他的意願行事——比如逼她放棄穩定工作到另一個城市。

這個家所有好處——被三個孩子叫爸爸、有一個像保姆的妻子幫忙打理生活、妻子的母親不得不幫忙——都與他相關。而所有壞處——貧窮、孩子照護、哭鬧、家務與日常痛苦——都只與艾瑪、艾瑪的母親與她的閨蜜相關,而與他無關。

在艾瑪死後,她仍能倒在另一個女人懷裡表演失去妻子的痛苦與無奈,以獲得未來妻子的憐憫與照顧。這樣的場景揭示了另一種結構性壓迫:父權不僅讓女性死於婚姻,還讓她的死亡成為一種被消費的情緒語境。在現代醫療系統中,身體疾病被簡化為腫瘤與症狀,而壓迫的成因——如慢性壓力、系統性忽視、情感剝削——不會出現在醫療記錄中,法律也不判處造成這種壓力的人。這種去政治化使得結構性壓迫被遮蔽為個人悲劇。

在艾瑪死後,她仍能扑在另一個女人的懷裡,表演自己失去妻子的痛苦與無奈,以獲得未來妻子的憐憫、照顧和心疼。彈幕上最高讚的一句話是:「安娜,你的愛太廉價了。你把所有的痛都留給了最愛你的媽媽。」第二高讚的一句話是:「不嫁給這個男人,她就不會死。」而一切又與她自己的一意孤行和絕不悔改捆綁在一起。

現代醫學讓亞洲女性也看到了,女人身上的病大多是「氣出來的病」。而「氣出來的病」,法律是不會判這個男人受刑的。即便在今天的美國也是如此。仍有一些對婚姻和愛情抱有期待的人說:「原來不愛你的人,哪怕你得了絕症,他也不會有一點心疼。」不愧是獲得奧斯卡獎的電影。它真實地展現了這個男人在出軌之前的流氓自私,以及出軌之後,知道妻子罹患惡性腫瘤,仍能呼呼大睡、飲食暢快、與出軌對象联席,而對三個孩子不管不顧,一次吃掉一大餐盤食物。他也不會擔心得了惡性腫瘤的妻子在醫院裡要經歷怎樣的痛苦。只有艾瑪的母親在醫院裡瘋狂地大叫:「給我女兒打無痛針!」

我想起來一個女人:馬茸茸,在2017年8月31日晚上,她在陝西省一家醫院待產時,帶著肚子裡的孩子赤裸的從醫院的五樓跳下去自殺了。 馬茸茸的孩子胎大難產。他數次要求剖腹產,要求打無痛。 有影片顯示馬蓉蓉給丈夫還有家屬下跪。這裡醫院和丈夫延壯壯出現了兩種不同的說法,大多數人相信的是第一種,因為馬茸茸作為一個女性,她想要打無痛,必須得有親屬簽字,也就是她的丈夫。或他的媽媽。 但是因為她嫁給了她的丈夫,她連打無痛的權利都沒有了。而他的媽媽也並沒有理會女兒的「打無痛」的請求。 因為當時馬蓉蓉的婆婆也在。據說是這個婆婆不允許馬蓉蓉打無痛,因為擔心打無痛影響孫子的出生。 這個版本的答案是最符合東亞的敘事的。因為在大多數的東亞家庭看來,娶一個老婆就是為了獲得孩子,那麼這個老婆的痛苦是不重要的。而且,剖腹產會影響二次生育。剖腹產也需要花更多的錢。因為在許多東亞人看來,女人生孩子是天經地義的,女人受苦也是天經地義的,女人被看作生育工具,所以她所承受的痛苦是不重要的。能夠順利地生下孩子,能夠更便宜地生下孩子,才是他們的想要的。 也就是丈夫延壯壯一再拒絕打無痛導致了馬茸茸絕望跳樓。

另外一個版本是延壯壯說的。延壯壯說醫生一再拒絕馬蓉蓉進行無痛分娩,並告訴他們可以自然分娩。所以他們才沒有打無痛。

我們能看到證據中有視頻,馬茸茸確實有走出產房三次對著她的丈夫下跪。 根據她丈夫的說法,那是因為痛得站不住了,才跪下,並不是下跪。 雖然不清楚害死馬柔柔的是不是她丈夫想要少花錢,忽視女人的痛苦,一定要逼迫馬茸茸順產。 但醫院確實有多次記錄馬茸茸的丈夫拒絕剖腹產的記錄,而且網路上有嚴壯壯按下指紋的順從知情同意書。醫生護士作證多次向馬蓉蓉的丈夫說明需要剖腹產,但都被延壯壯拒絕。 在媒體採訪的時候,延壯壯稱呼馬茸茸是產婦而不是我老婆我老婆。不管怎麼樣,最後由於事情鬧得很大,延壯壯得到了一大筆賠款。 產婦的死亡讓他出了名, 且馬茸茸也是和延壯相親閃婚。 (註:相親解釋)馬茸茸死前說自己選錯了。且後來的訪談中延壯壯和母親並沒有半滴眼淚。由於法院審理認為醫院沒有看管好產婦(阻止跳樓),所以延壯壯還拿到了醫院賠償金很快再婚了,並且娶妻又生子了,幸福又美滿。

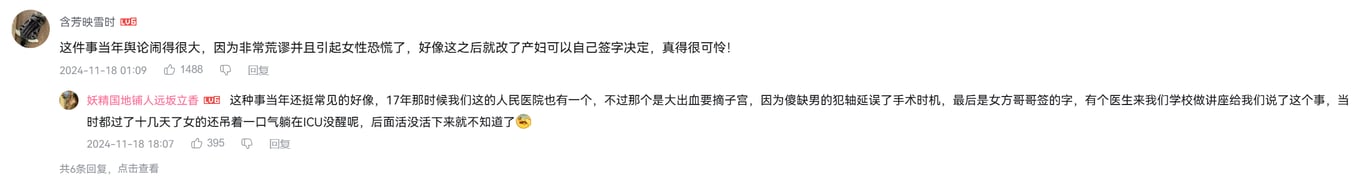

2017年,馬茸茸跳樓以前,為了省錢和方便快速生二胎,甚至在緊文化下的男性虐待欲影響下,不給產婦打無痛分娩是一種常見現象。此時,丈夫甚至可以和母親一起羞辱妻子,責備她“嬌情”,說以前的女人都是這樣生的,怎麼就你大驚小怪。這種行為反映了東亞父權下的結構性控制與女性生育自主的剝奪。2017年8月31日,馬茸茸跳樓之後,中國女性才正式獲得自己決定能否使用無痛分娩以及是否剖腹產的簽字權。

在馬茸茸事件的留言中,大量華人女性分享了自己在產房中遭遇的恐怖經歷。這一刻,東亞男性平日沉默寡言、隱藏在社會規範背後的真面目突然顯露出來:他們認為自己可以決定“保大還是保小”,認為與東亞女人結婚,就能掌控她們的生死與命運。無論是艾瑪的案例,還是馬茸茸的案例,妻子的死亡都能給丈夫帶來更好的生活,這也呼應中國流傳的一句話:中年男人最值高興的三件事——升官、發財、死老婆。另一句仍在使用的話是:“打到的媳婦柔順的面”,反映父權對女性服從和痛苦的美化。

不管是艾瑪還是馬茸茸,她們都在父權制的規訓下隱藏著真相,看不清丈夫的真面目。馬茸茸2017年8月的跳樓事件,才換來中國女性在產科決策中獲得簽字權,也讓女性明白,所有權力都必須靠流血與犧牲爭取,而不是靠父權施舍。父權灌輸給女人的忍讓與愛,換來的只能是地獄式的痛苦與剝奪。

All Rights Reserved© 2025 Jules Vela,Copyright, intellectual property, and all derivative rights of the Work are fully owned by Jules Vela.Without written permission from Jules Vela, any form of reproduction, reprint, quotation, excerpt, adaptation, rewriting, translation, uploading to the Internet, or use in any publications, websites, social platforms, or media channels, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.No individual or organization may use the content of the Work for commercial, academic, or non-commercial purposes. Unauthorized use will be considered infringement, and legal action will be pursued in full.The Work is protected under international copyright law, including but not limited to the Berne Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, and other relevant laws and regulations.This chapter belongs to: Dark Disease; all rights are exclusively owned by Jules Vela.Any violation of this copyright statement constitutes infringement. The copyright holder reserves the right to take legal action, including but not limited to civil compensation, criminal prosecution, and administrative penalties.

The Chinese title of this film shocked me once again. It was translated as Terms of Endearment into “Deep Mother–Daughter Love.” But in reality, this film is not merely about a mother–daughter relationship. It is about intimacy itself. So why was the focus deliberately shifted — narrowed — from male emotional coldness, selfishness, and incapacity for intimacy into a story about mother–daughter bonds? Because that framing does not offend patriarchy. Mother–daughter affection is a safe, domesticated, depoliticized theme. One man’s selfishness ends up exhausting an entire group of women.

This film has never been only about motherhood or daughterhood. It is about the systemic cost women pay when they invest their lives, bodies, and futures into the wrong intimate relationships. Between Emma and her mother Aurora, there are undeniably control dynamics, conflicts, authoritarian tendencies, and power imbalances. Yet at the same time, theirs is a form of love that is real, continuous, and action-based — a love that does not disappear in moments of crisis. In brutal contrast stands Emma’s marriage: the relationship labeled as “love” that completely absents itself at the most vulnerable moments of her life.

Whether they are East Asian men or white American men, they are remarkably skilled at relying on patriarchy and social systems to perform “love” with minimal effort. Simply by possessing a male sexual organ, by ejaculating, they can become husbands and fathers — without being required to carry any responsibility that true intimacy demands.

Does Emma’s husband love her? If we continue to use the patriarchal definition of “love” — not hitting her, not divorcing her, occasionally coming home — then perhaps he qualifies. But if love means responsibility, shared burden, care, emotional responsiveness, and risk-bearing, then the answer is no. This man, Jack, is sensitive, self-centered, emotionally volatile, and consistently evasive of responsibility. He persistently transfers life’s risks onto Emma. His fantasies of family are, in essence, fantasies of free female labor and unconditional emotional supply. Emma did not reject her mother’s advice to leave because she was foolish, but because society repeatedly told her: “If you choose the right man, manage your family well, and raise your children properly, happiness will follow.” This is not an individual failure; it is structural indoctrination.

Although this film was made in 1983, by 2025 the husband in the story has once again been whitewashed under the logic of “East Asian-style male innocence.” When contemporary discussions avoid male accountability and instead allow men to narrate and interpret this film, male wrongdoing is rendered astonishingly mild. Even so, I still want to speak about what this film evokes in me.

What I see in this film is women caring for women, women supporting women — and the unsettling realization that white American men in 1983 and East Asian men today are structurally and behaviorally similar. Between Emma and her mother Aurora, there are undoubtedly control dynamics, authoritarian tendencies, and power imbalances, yet Aurora’s love for her daughter is undeniably real. But what about the husband? Does he love Emma? He acts on impulse, is sensitive, self-centered, selfish, and foolish. Driven by fantasies of love and marriage, by the desire to possess a “home of his own,” Emma decisively rejected Aurora’s advice to leave and chose Jack as her imagined partner in building that future “home.” The film presents, with startling clarity and directness, the horror of women blindly entering marriage. As a woman, Emma cheerfully presses the button that starts the countdown to her own death.

At that time, the patriarchy had promised Emma that if she found a man who sincerely managed the home with her, she would receive happiness and love. If he properly raised your children, you would achieve the “Happy Family”! But what was the truth? The truth is: when a woman enters an irrevocable marriage, the enormous sunk costs of that marriage can inevitably drive a woman toward death.

Emma was innocent and strong. She bore three children and faced the various difficulties and crises of life on her own. The man she chose was always cold and capricious, creating obstacles in her so-called home that would ultimately contribute to her death.

How do the “sunk costs” of marriage push women toward disease and death? Modern medicine has long indicated that chronic emotional suppression, helplessness, and prolonged stress are strongly correlated with a range of female high-incidence diseases, including but not limited to: breast nodules, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, immune system disorders, and cardiovascular diseases. Emma’s life serves as a standard case study. Her endurance did not change the marriage; it only transformed into malignant tumors within her body. She bore three children, long-term poverty, her husband’s betrayal, and emotional neglect. These were not “unfortunate events,” but the normal operation of marital structures. The law does not prosecute men who “drive women to death with anger,” and the medical system only records tumors, not oppression. For women, the sunk costs of marriage are not only financial and temporal, but also bodily, health-related, and involve social exit rights.

Emma’s endurance did not change her life; all the hardships she experienced after marriage came from this man. However, at that time, the patriarchy made her believe that as long as she was submissive and endured, happiness would surely follow. Thus, even when she witnessed the man’s infidelity, his coldness toward her, and heard him say he had no feelings for her, even though he deceived her for a transfer that was actually for another woman, making her move along with him, she still forgave his betrayal at the moment of her death. Recently, many Chinese women have watched this film and saw themselves in it. Online comments cursed Emma, claiming she deserved it, blaming her for choosing this man, choosing to bear one child after another, and said that since he ultimately expressed love for his son, she did not deserve pity. I cannot accept that she never saw the truth in the end. To die tragically without seeing the truth is the norm under patriarchy.

How horrifying, the lies of patriarchy drove her to death, yet she still loved this man. Even though, in her life, every danger was handled by her mother, herself, and her close friends, she gave all her beauty to this man, while giving all her resilience and true self to her friends and mother. Her husband was indifferent when he heard of her malignant tumor. One could even sense a sigh of relief, a secret joy in being blessed by God to marry a woman who was unfaithful. Online discussions focused largely on his eldest son. Women were shocked by the terrifying “inferior genes,” warning not to have children indiscriminately. A father’s deficient genes could perfectly pass to the son; a father’s indifference and abuse toward the wife could also be transmitted to the son. The so-called “inferior genes” panic is, in essence, an intuitive fear of the intergenerational replication of patriarchal behavior. Jack could sleep calmly, like a dead pig, on the eve of his wife’s death because he could see a bright and beautiful future. The mother, Aurora, who had always hated Jack, cried on his chest after her daughter’s death, which I found extremely ironic. At that time, medical knowledge was insufficient, and she could not see who had truly caused her daughter’s death. Some systems never intended for women to survive. Some men can “kill their wives without bloodshed” and receive sympathy.

Marriage as Gendered Sunk Cost and Women’s Health Burdens

Marriage as Gendered Sunk Cost refers to the structural condition in which women invest irreversible time, emotional labor, caregiving work, and bodily risk into marriage—investments they cannot retract once made. This sunk cost is gendered rather than neutral, as women are expected to shoulder the majority of domestic duties, childcare, emotional support, and crisis management while men often reap the benefits. Research indicates that stress overload may mediate health disparities associated with marital quality, suggesting that long-term emotional and psychological burdens have concrete effects on health.

Throughout the film, it is women caring for women, with Emma’s friends and mother taking responsibility for the children and her care, while the man enjoys the results. The husband’s calm relief upon learning of her terminal cancer is nauseating. He does not panic, break down, or lose sleep. To him, the future appears lighter. Aurora cries on his chest after her daughter’s death.

This exemplifies the success of patriarchy—it trains even a grieving mother to comfort the beneficiary, projecting her love onto the man and assuming he will regret his actions, rather than holding him accountable. In reality, this man is pleased; Emma dies at the “appropriate” moment.

Chronic Stress, Disease, and Breast Cancer Risk

Medical research shows significant associations between chronic psychological stress and disease, particularly in relation to cancer. Chronic stress dysregulates the neuroendocrine and immune systems, contributing to tumor development and progression. Recent studies highlight the biological mechanisms by which chronic stress influences breast cancer, including sustained release of stress neurochemicals that may promote tumor growth and affect prognosis.

Specifically, chronic stress is recognized as a major risk factor in the development and progression of breast cancer, mediated by psychological distress leading to dysfunction in cellular and molecular pathways.

Patriarchy and Women’s Bodily Toll

When Emma was terminally ill, her friends tried to lift her spirits by reconnecting her with others. Women who chose abortion or divorce remained socially visible and “successful.” Only the woman who endured, persisted, and clung to a marriage despite infidelity remained trapped in the illusion of marital stability. Trying to bind her husband with more children, Emma, after bearing three children, developed malignant cancer. This reflects a patriarchal myth that endurance leads to reward and fulfillment.

After her diagnosis, the care for Emma and her children came from women—her mother and her friends. Whether she followed Jack to another city or struggled with post-marriage chaos, poverty, and maternal punishment, the hardships appeared unrelated to him. He focused on enjoying life, pursuing his desires, and even used humiliation, blame, and coercion to make her act according to his will—forcing her to abandon a stable job for relocation.

All the benefits—being called “dad” by his children, having a wife handling domestic tasks, and receiving help from his mother-in-law—belonged to him. All the burdens—poverty, childcare, tantrums, housework, and daily struggles—fell solely on Emma, her mother, and her friends.

Medical–Legal Depoliticization of Oppression

After Emma’s death, she could still collapse into another woman’s arms to perform sorrow and helplessness, garnering pity and care from a future spouse. This illustrates another layer of structural oppression: patriarchy not only allows women to die within marriage but turns their deaths into consumable emotional narratives. Modern medical systems reduce bodily disease to tumors and symptoms, failing to document root causes such as chronic stress, systemic neglect, and emotional exploitation. Legal systems do not prosecute individuals for creating such stress. This depoliticization masks structural oppression as personal tragedy.

After Emma's death, she could still collapse into the arms of another woman, performing her grief and helplessness over losing her wife, in order to receive the pity, care, and attention of a future partner. One of the most liked comments on the forum was: “Anna, your love is too cheap. You left all the pain to the mother who loved you the most.” The second most liked comment was: “If she hadn’t married this man, he wouldn’t have died.” All of this, however, is intertwined with his obstinate self-will and absolute lack of remorse.

Modern medicine has shown Asian women that many of the illnesses women suffer from are “stress-related illnesses.” Yet such “stress-related illnesses” do not result in legal consequences for the man. Even in present-day America, this remains true. Some who still hold expectations about marriage and love have said: “It turns out that someone who doesn’t love you won’t feel any grief even if you are terminally ill.” This film, rightfully awarded an Oscar, vividly portrays this man’s selfishness and cruelty before his affair, as well as his complete indifference after knowing his wife had a malignant tumor. He could still sleep soundly, eat well, and pursue his affair, while ignoring his three children entirely, eating large plates of food without concern. He did not worry about the suffering his wife would endure in the hospital from the malignant tumor. Only Emma’s mother frantically shouted in the hospital: “Give my daughter a painless injection!”

-On the night of August 31, 2017, Ma Rongrong committed suicide by jumping from the fifth floor of a hospital in Shaanxi Province while in labor, carrying her unborn child. Her baby was too large, causing a difficult delivery. She repeatedly requested a cesarean section and requested epidural anesthesia. Video evidence shows Ma Rongrong kneeling before her husband and family members, pleading for assistance. There are two conflicting accounts from the hospital and her husband, Yan Zhuangzhuang. The first, widely believed, is that as a woman, Ma Rongrong needed a relative’s consent—her husband or mother-in-law—for the epidural. However, after marrying, she was denied this right, and her mother-in-law reportedly refused due to concerns about affecting the child’s birth. This account aligns with East Asian cultural narratives, where a wife’s primary role is to bear children, and her suffering is considered secondary. Cesarean sections are more costly and may impact future fertility. In such a cultural framework, women’s pain is devalued. Yan Zhuangzhuang’s repeated refusal of epidural anesthesia drove Ma Rongrong to despair and ultimately suicide, exemplifying how marital sunk costs directly erode female rights and health.

The alternative account, presented by Yan Zhuangzhuang, claims that doctors repeatedly refused epidural anesthesia and advised vaginal delivery, so it was not administered. Nevertheless, evidence shows Ma Rongrong knelt three times outside the delivery room. Her husband claimed this was because she could not stand due to pain, not a proper kneeling. While it is unclear whether her death was directly caused by her husband’s desire to minimize costs or disregard for her pain, hospital records confirm multiple refusals of cesarean requests by the husband, and online records include fingerprinted consent forms he signed refusing surgery. Medical staff testified that they repeatedly explained the necessity of cesarean delivery, but he refused each time. In media interviews, Yan referred to Ma Rongrong as a “patient in labor” rather than “my wife.” Ultimately, the case gained public attention, he received financial compensation, and Ma Rongrong tragically died.

It is important to note that Ma Rongrong and Yan Zhuangzhuang had a matchmaker-arranged rapid marriage. In East Asia, “matchmaking” is not equivalent to Western blind dating. It involves formal introductions arranged by family or friends, emphasizing practical marital concerns and family approval over romantic choice. This context highlights the structural sunk costs of marriage and the institutional deprivation of women’s rights. Before her death, Ma Rongrong admitted she had chosen the wrong partner. Neither her husband nor mother-in-law showed grief. The court ruled that the hospital failed to adequately monitor the patient to prevent suicide, allowing Yan Zhuangzhuang to obtain compensation from the hospital. He subsequently remarried and had children, leading an happy life.

Before Ma Rongrong’s suicide in 2017, it was common for men to deny pain relief during childbirth, in order to save money, expedite the delivery of a second child, or under the influence of tight culture, latent abusive tendencies. At this time, husbands could even join with their mothers in shaming their wives for being “too delicate,” claiming that women in the past gave birth in the same way, and asking “why are you making such a fuss?” This behavior reflects structural control under East Asian patriarchy and the deprivation of female reproductive autonomy. On August 31, 2017, after Ma Rongrong jumped from the hospital, Chinese women officially gained the legal right to decide whether to use epidural anesthesia and whether to undergo cesarean sections—a critical milestone in maternal autonomy.

In the comments following the Ma Rongrong incident, many Chinese women shared their own terrifying experiences in delivery rooms. At that moment, the true face of East Asian men—usually hidden behind social norms and silence—became starkly visible: they felt entitled to decide whether to “save the mother or the child” and believed that marriage to an East Asian woman granted them control over her life and fate. Whether in the case of Emma or Ma Rongrong, the wife’s death could bring a better life to the husband. This is reflected in a popular Chinese saying: “Three happiest things for middle-aged men—promotion, wealth, wife’s death.” Another still-used phrase is: “The beaten wife shows a compliant face,” reflecting the patriarchal glorification of female submission and suffering.

Neither Emma nor Ma Rongrong could see their husbands’ true nature, as they were obscured by patriarchal discipline. It was Ma Rongrong’s suicide on August 31, 2017, that allowed Chinese women to gain the right to sign for themselves in childbirth decisions, showing that all power must be fought for through blood and sacrifice, not given by patriarchy. The obedience and love instilled by patriarchy in women can only result in hellish suffering and deprivation.

Reference List (APA 7th)

Hamer, M., Endrighi, R., & Poole, L. (2021). Chronic stress and breast cancer risk: A systematic review. PubMed. Retrieved from pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih....

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Gouin, J. P., & Hantsoo, L. (2022). Psychoneuroimmunology and marital stress: Chronic stress and health outcomes in intimate relationships. PubMed. Retrieved from pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih....

Li, X., Zhang, Y., & Wang, H. (2024). Effects of chronic stress, anxiety, and depression on breast cancer development: Evidence from Chinese cohorts. Journal of Clinical Oncology Research, 12(9), 1303–1315. Retrieved from journal11.magtechjou...

James H Amirkhan 1, Alissa B Vandenbelt 1(2023)Marriage and health: exploring the role of stress overload https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36067057/

Hui-Min Liu 1, Le-le Ma 1, Chunyu Li 2, Bo Cao 3, Yifang Jiang 4, Li Han 1, Runchun Xu 5, Junzhi Lin 6, Dingkun Zhang 7(2022)pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih....

SU Lingfeng1, WANG Huxia2, WANG Yanfeng3, SONG Zhangjun3* (2024)Impact of chronic stress on the development of breast cancerhttps://journal11.magtechjournal.com/Jwk_jcyxylc/CN/10.16352/j.issn.1001-6325.2024.09.1303?utm_source

Marriage as Gendered Sunk Cost — Women’s Path to Illness and Mortality

Author: Jules Vela | © All Rights Reserved

I. Conceptual Definitions

Marriage as Gendered Sunk Cost

Refers to women’s irreversible investment in marriage, including time, energy, financial resources, physical health, and social exit rights. Once committed, these resources cannot be fully recovered and create long-term psychological and physiological burdens for women.

Bloodless Male Violence

Refers to non-physical forms of male violence within marriage and family, including emotional indifference, power manipulation, responsibility evasion, and economic oppression, which cumulatively can result in chronic illness or mortality for women.

Female Caregiving Burden

Refers to women’s unpaid caregiving responsibilities in the household and society, including caring for children, partners, parents, or other female relatives, which entail emotional, physical, and social costs.

II. Case Study: Emma

1. Invisible Costs Carried by Women

After Emma’s death, she was still able to collapse into the arms of another woman, performing her grief and helplessness to gain future wives’ pity, care, and concern. The most liked comment on online discussion boards was: “Anna, your love is too cheap. You leave all the pain to the mother who loved you most.” The second most liked comment was: “If you hadn’t married this man, he wouldn’t have died.” Yet all of this remains bound up with his obstinacy and refusal to repent.

Modern medicine has made it visible to Asian women that many women’s illnesses are “stress-related diseases.” Yet the law will not punish the man responsible for these “stress-induced illnesses.” Even today, in the United States, there are still people who hold expectations about marriage and love, claiming: “Even someone who doesn’t love you will not feel a single shred of sympathy if you are dying of a terminal illness.” This Oscar-winning film accurately portrays this man’s selfishness before his affair, and after discovering that his wife had a malignant tumor, he still slept soundly, ate freely, and practiced with his extramarital partner, neglecting his three children and devouring a large plate of food. He did not worry about the suffering his terminally ill wife endured in the hospital. Only Emma’s mother screamed frantically in the hospital: “Give my daughter a painless injection!”

2. Pathological Norms Under Patriarchy

Men can profit from marriage without shedding blood, while women bear all emotional and physical costs. Emma’s patience and compliance did not alter her marriage; instead, it transformed accumulated stress into malignant tumors. Contemporary medical research has shown that chronic stress and emotional suppression are highly correlated with breast cancer, ovarian cancer, immune dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2022; Hamer et al., 2021). This illustrates the lethal effects of gendered sunk costs in marriage.

3. Medical–Legal Depoliticization of Gendered Oppression

Healthcare systems only record diseases, and legal systems only determine whether behavior constitutes criminality, but neither system adjudicates the structural violence of male emotional indifference, family control, or marital abuse that leads to chronic illness or death in women. This depoliticization allows gendered sunk costs and male violence to remain invisible. Even when women develop “stress-induced illnesses,” the law remains powerless, while men continue to enjoy life and privileges (Umberson et al., 2010; Thoits, 2010).

III. Discussion and Theoretical Implications

Emma’s case demonstrates a threefold stress structure of marriage as a gendered sunk cost:

Physiological Stress Accumulation: Chronic emotional suppression leading to physiological illness.

Psychological and Social Stress: Women bear the entirety of caregiving burdens.

Legal and Institutional Ineffectiveness: Male violence remains unpunished.

Women’s health and lives are systematically weakened, with patriarchy naturalizing this violence through marriage and family structures. Public health policy should consider familial stress and marital structural pressures in addressing women’s health (Thompson et al., 2017).

IV. Conclusion

Emma’s experience reminds us that marriage, for women, is not merely a social role or emotional choice but an irreversible investment — a gendered sunk cost — potentially resulting in chronic illness or death. Patriarchal structures transfer costs to women, and the depoliticization by medical and legal systems perpetuates this structural violence.

References

Hamer, M., Kivimäki, M., & Steptoe, A. (2021). Chronic stress and cardiovascular disease: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 1–18. doi.org/10.1146/annu...

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Wilson, S. J., & Bailey, M. L. (2022). Chronic stress and immune function in women: Implications for disease susceptibility. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 138, 105622. doi.org/10.1016/j.ps...

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R., & Reczek, C. (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. doi.org/10.1146/annu...

Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(S), S41–S53. doi.org/10.1177/0022...

Thompson, E. H., & Walker, A. J. (2017). Gender, work, and family health: A public health perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 190, 198–205. doi.org/10.1016/j.so...

Originality Statement

This chapter and all content are the original creation of the author, Jules Vela. All rights are reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, used, or cited without the explicit written permission of the author for any publication, academic, educational, or commercial purpose.

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!

- 来自作者

- 相关推荐