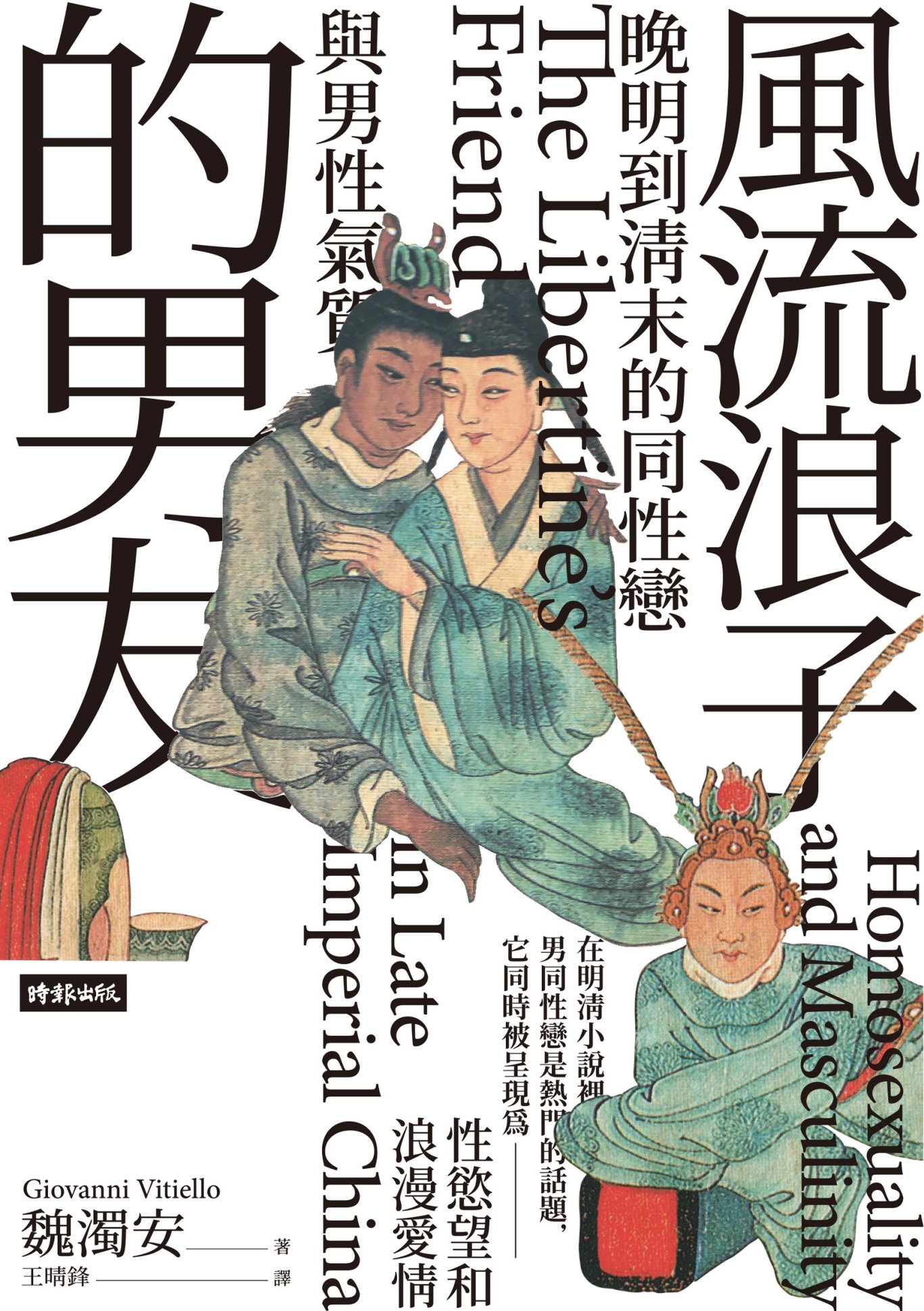

draft《giovanni vitiello》读

舊時代將男子的經業稱為「精華」。 最好笑的是用「龍」「陽」來指同性戀。 更好笑的是,在清朝,龍陽之後是一個雅後,包括賈榮、賈寶玉都是隨時把同性戀的葷段子掛在嘴邊。 他提出:「龍陽已經累化到一般人的生活中,江南文化如陽州市井。至今任以『不龍陽』來評價事物不可愛。甚至炫耀稀奇可愛之物時,就會問:『你看!龍陽不龍陽?』」我最沒想到的是,在二十世紀初,軍政險要都喜好。也就是說,在民國的時候,如果你要拍民國戲的話,那些軍閥喜歡的不是女性,而是男性,特別是那些唱京劇的人。 男妓之類的。 晚明的時候,還有幽靈的品嚐。喜好藍色被看作是一種高級的美感和興趣,為優雅的標誌。 我覺得最有趣的是,這本書有講到儒家男性的氣質。 儒家男性棋子是所謂的儒士,也就是所謂的年輕學子寒門才子。專攻這個才子家人的小說,也就是說在古代的時候,之所以才子這樣一個沒有信章歷的形象得到推崇,也有可能是因為寫書的大部分都是儒生。 也就是說,他們自己美化了自己的形象。 最好笑的是,從明朝開始,男性的菊花不可插入。被插入的是女性或少年,在文中一般少年會被看作賤人。到清朝時期,男性本身也可以被插入。 也就是說,一個人的性別、性行為、性意識都是嚴格地受到政治體制的影響、監控、以及規訓的。 然後,雍正年間(1723年到1735年),這個清政府試圖透過更嚴格的男女法律的邊界來幹預性別意識的形態。 最有趣的是,在這一個時期,色情小說中出現了新的傾向。酷愛南風的人物角色逐漸被遮蔽,從故事裡面抹去。而且在最極端的情況下,還會被斬首。也就是說,像這樣的男性在這個時期就不能再當主角了。 我不清楚當時的男性是因為對這種陽剛氣質的喜歡,認為男性是尊貴的,也就是一種自戀投射。

還是說,他們真的就是極度在這個文化和環境的烘托下,大部分的人變成了同性戀。 我們可以觀察到的是,在這本書中寫到18世紀末19世紀初,很多人會去欣賞藍色,並且製作這個男旦的美貌和才藝的花譜。 本書裡提到的很多明清的同性戀小說,我是有看的。但我不知道是那個時期的小說太少了,還是怎麼回事。可能是太少了吧。我沒有想到這幾本剛好都看過。

就是因為以前有一些小姐姐們在總結這個單美書單的時候,會特別提到這些書。其實字數也不多,所以說可能那時候的人是實踐派吧,因此寫的小說不多,直接都是去捧這個男蛋。

不知道那個時候的愛滋病是不是也是高發生率。 這個馬克夢是最早研究明清小說中男性氣質演變的學者之一。根據他的發現,《萬民》的小說裡,男性角色越來越出現嚴重的女性化傾向。

這導致了在歷史和武俠的敘事裡,風流壓倒了好漢。 我覺得這個還蠻好笑的。就是因為拿筆的人是比較瘦弱的女性化的人,所以說對於該事蹟的記錄就變成了這個風流的書生是主角,是主流。

但是不清楚當時真實情況是怎麼樣。 在研究女性主義的時候,有一本很著名的書提到,在民國時期,中國才開始聽到關於愛的說法。 在這本書中,作者談到明清小說作品裡,男同性戀被呈現為性慾望和浪漫愛的結合。也就是說,他們同時具備生理上的喜歡和情感上的喜歡,這還蠻神奇的。因為我們基本上沒有看到對於女性的浪漫愛情,通常都是一種書生見色起意的表現。 我覺得比較有趣的是,現在有很多文章會強調這個去雄化是其他勢力的陰謀。

但是我們可以看到,這種去雄化的美學從清朝就已經開始了。因為那些乳生都很瘦弱,所以他們的主角或是他們所建構的男性氣質,就是女性化、柔弱的男性形象。 不是今天才開始東亞男性的體格是比較瘦弱的,而是最起碼從這本書看來,從明朝開始就一直是以那種書生穩弱的狀態為美的標準的。 《紅樓夢》裡面就更明顯了,你基本上就沒看過任何一個正面的男性角色是強壯的。 有專門提到在公元四世紀的儒家經典《孟子》講到“時、色、性也”的這個“性也”,以及這個“色”,它是個中性詞,未規定性意對象的性別。

而且在一直以來的文學作品中,都會提到男性既貪女色,幼木難封,甚至酷好男風,以及出門去尋找漂亮的美少年,走漢道的相關記錄。 而且最有趣的是,孟子提到古代傳奇式的美男馮子都,並且提到馮子都的美貌讓人無法抵禦他的誘惑,甚至捨不得閉上眼睛。 而且,《姑妄言 》邊還記錄了崑山地區出現男妓高度聚集的現象。認為當地人對漢路的性傾向是由於他們祖先被埋葬在水中。

《載花船》《再活川》裡面有一個男子生平喜好龍陽,而且是極度喜好龍陽。

他最後愛上了一個偽裝成太監的女人。 《肉蒲團》當中有一節《別有鄉》,裡面的故事解釋了什麼是「家童」。 在許多小說中,由於性慾的獵奇心理或權宜之虛,他們會與少年發生性關係。 而風流浪子通常與年輕的弄臣或弄童結伴出遊。 這些能夠起到解憂和撫慰心靈的作用。 然後,晚明的文人沈德符描述了他生活的年代空前的流行——男色和男妓。 帝國晚明的文獻:常採用烹飪和植物的隱喻,顯示將心吸引看作如同味道和氣味那樣的感官體驗。 花式用來表示感官美的標準方式。後庭花式明確指的是「當門」。機間通常被形容為“別有香”。 李漁的《無聲戲》裡居然有一個主角讚美了少年的純潔,而且說到少年的純潔是沒有女人的嬌柔造作的。 有趣的是,在這本書裡,你可以看到它提到,對於古代的男性來說,他們的性行為也是一種特權。這並不是互動性的,因此這也是一個值得探討的奇特之處。

本書裡非常直接地寫到,在明清時期的人們看來,雖然對於酷號「南風」之人來說,他們的年輕伴侶的少年有很多名稱用於含糊地描述不同的情景和關係的類型,但利益是最重要的。

但是奇怪的是,比如說像秦鐘和賈寶玉,以及另外西的和賈寶玉的關係,是沒有捲入經濟交易的。因為在古代的人看來,這樣的話會讓關係變得惡俗。

不過,有很多文獻會記錄男性去找男妓的行為。這樣行為雖然說是不高雅的,但它是一種享樂和消遣。 然後明末呢,明顯可以看到真正的南風興起,在江南地區尤為如此。

吳存存和郭安瑞指出,隨著京劇以及男旦的興起,男妓之風可能在18世紀末19世紀初的北京達到了頂峰。 利瑪竇更是生活在福建,但他一生中大部分時光是在北京度過的。衛匡國非常熟悉浙江,在他的《中國新圖志》(Novus Atlas Sinensis)裡,指出溫州和福建的漳州是這種「反常的性慾」最為顯著的地方。利瑪竇更是生活在福建,但他一生中大部分時光是在北京度過的。衛匡國非常熟悉浙江,在他的《中國新圖志》(Novus Atlas Sinensis)裡,指出溫州和福建的漳州是這種「反常的性慾」最為顯著的地方。

Structural Parasitism and Historical Extraction in East Asia

Author: Jules Vela

Email: [email protected]...

Project: Dark Disease

Project: Dark Disease

December 26, 2025

© All Rights Reserved

1. Core Structural Concepts

1.1 The Parasitizing King /

Original Concept

The Parasitizing King is not a conventional monarch. He functions as the central suction point of the political-economic apparatus. All economic, military, penal, ritual, bureaucratic, and epistemic power converges into this single node, turning society into a centralized extraction funnel. Institutions are not designed to govern in the conventional sense, but to feed this parasitic node. This system allows infinite extraction with zero accountability, converting populations into consumable material.

1.2 The Parasitizing Caste

Original Concept

The Parasitizing Caste supports the King. Its existence relies on hereditary privilege, bureaucratic authority, and cultural legitimation (rituals, Confucian canon, moral codes). This caste is the operative structure that enforces extraction, administers governance, and morally justifies parasitism.

1.3 Enslaving Human Livestock

Original Concept

Enslaving Human Livestock refers to the institutionalized lower population, treated as a renewable supply of labor, reproductive potential, and consumption for the parasitic center. Historical examples include famine-induced sale of family members, wartime sacrificial provisions, and ritual consumption recorded in oracle bones and Zhou texts. This was not episodic but normalized, affecting the majority of the population.

1.4 Enslaving Human Essence

Original Concept /

Enslaving Human Essence is the extraction of intangible human capital: emotional labor, cognitive time, moral and psychological energy, and reproductive capacity. Confucian moral domestication, corvée systems, household registration, civil examinations, rituals, and legal punishment together institutionalized the voluntary or internalized supply of these essences to the parasitic caste.

2. Systemic Model: Purgatory Funnel-History Model

Original Concept

The Purgatory Funnel-History Model describes cyclical extraction in East Asian dynasties:

1. ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK are systematically extracted.

2. Resources flow upward to sustain the Parasitizing Caste and Parasitizing King.

3. When extraction exceeds a critical threshold, social unrest or uprisings occur.

4. Old parasitic structures collapse, but new parasitizing kings or castes emerge.

5. The funnel restarts, maintaining continuity of systemic parasitism.

The Parasitizing Pyramid of East Asian Historical Extraction

Original Concept

The Parasitizing King is not simply an emperor. He occupies the apex of the political system’s resource funnel. Economic, military, legal, ritual, bureaucratic, and epistemic powers all converge into this node, transforming society into a stable extraction pyramid. The institutional function is not governance but to feed the parasitic center, converting the population into consumable resources.

“以天下供養一人,天下的子民都是東亞皇帝的子民。那麼子民的一切都屬於皇帝。” This reflects that all social production and human capacity were formally extracted for the sovereign.

The Parasitizing Caste refers to the bureaucratic and noble strata that live off the extraction of ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK and ENSLAVING HUMAN ESSENCE, which includes all measurable and intangible resources—time, energy, labor, and life itself, including members of this caste.

Historical scale: In the late Ming dynasty, just the noble clan network accounted for roughly 200,000–300,000 people, forming a massive extraction class. Consequently, before modern times, the ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK were extremely impoverished, often lacking basic clothing and food security, as confirmed by early photographs, black-and-white images, and historical records.

At the base of the pyramid lies the Edible Woman Caste, historically regarded as the most despised and consumable human resources under East Asian patriarchy. They were not only objects of trade but, in times of famine, literally used as food. In Chinese historical texts, such women were referred to as “不羡羊”—a literal consumption metaphor.

Original Contribution

:Parasitizing King → Parasitizing Caste → ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK → Edible Woman Caste

The Parasitizing Pyramid and the Purgatory Funnel-History Model

1. The Parasitizing King

The Parasitizing King is not a conventional monarch. He is the apex node of the political system’s resource funnel. Economic, military, legal, ritual, bureaucratic, and epistemic powers converge into this node, transforming society into a stable extraction pyramid. Institutions exist not to govern but to feed this parasitic center, converting human populations into consumable resources.

2. The Parasitizing Caste

The Parasitizing Caste is the bureaucratic and noble strata that sustains itself by extracting ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK and ENSLAVING HUMAN ESSENCE, including all time, labor, energy, and life capacity of the population—including members of the caste itself.

Historical scale: In the late Ming dynasty, noble clans alone accounted for 200,000–300,000 people, forming a massive extraction class. Consequently, ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK were extremely impoverished, often lacking clothing and basic nutrition, as early photographs and historical records attest.

3. Edible Woman Caste

At the base of the pyramid lies the Edible Woman Caste, the most despised and consumable human resources in East Asian patriarchy. They were not only objects of trade but, in times of famine, literally used as food. In Chinese historical texts, such women were called “不羡羊”, highlighting their consumable status.

4. ENSLAVING HUMAN ESSENCE

ENSLAVING HUMAN ESSENCE represents the extraction of psychological energy, emotional labor, reproductive capacity, cognitive time, and moral commitment. This is institutionalized extraction that transforms people’s internal capacities into supplies for the Parasitizing Caste. Mechanisms include moral domestication via Confucian norms, household registration, corvée, rituals, and legal systems enforcing self-surveillance through shame and social punishment.

5. The Purgatory Funnel-History Model /

The Purgatory Funnel-History Model describes a cyclical extraction structure: lower strata (ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK) are continuously extracted → resources sustain the Parasitizing Caste → when extraction exceeds tolerance, uprisings or systemic collapse occur → old parasitic structures fall, new Parasitizing Kings/Castes emerge → the funnel restarts.

Compared to Atlantic slavery or European feudalism, this model emphasizes:

1. Internalized moral consent—self-surveillance by the oppressed;

2. Institutionalized reproduction and population management;

3. Ritual-legal legitimization of extraction.

6. Hierarchical Structure and the Human Extraction Pyramid /

The Parasitizing Pyramid consists of three interrelated layers:

1. The Parasitizing King– A single apex node (1 person) who absorbs all economic, military, legal, ritual, bureaucratic, and epistemic resources. This figure is not merely a monarch but the terminal sink of the system’s extractive funnel. The doctrine of li chu yi kong (利出一孔, “let benefits flow from one orifice”) ensures that all societal output converges on this node.

2. The Parasitizing Caste Typically 5–10% of the population in early dynasties, this includes bureaucrats, nobles, and elite families. Over time, the caste expands as dynasties mature, consolidating wealth, administrative control, and social legitimization of extraction. They manage and oversee the base populations, distributing corvée, tax collection, ritual organization, and education that aligns the population’s behavior to the parasitic system.

3. ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK and Edible Woman Caste Constituting approximately 90% of the population, this stratum lived in extreme poverty and exhaustion, often worse than livestock. Besides heavy taxation, members were subject to intensive corvée. Women, on top of raising children, wove textiles, farmed during men’s labor rotations, and could be sold if the household lacked resources. The Edible Woman Caste occupies the bottommost layer of the pyramid as the most consumable assets, exposed to literal or symbolic consumption under extreme scarcity.

4. ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK and Edible Woman Caste Constituting approximately 90% of the population, this stratum lived in extreme poverty and exhaustion, often worse than livestock. Besides heavy taxation, members were subject to intensive corvée. Women, on top of raising children, wove textiles, farmed during men’s labor rotations, and could be sold if the household lacked resources. The Edible Woman Caste occupies the bottommost layer of the pyramid as the most consumable assets, exposed to literal or symbolic consumption under extreme scarcity.

Part 1: Historical Structure and the Human Extraction Pyramid

1. The Parasitizing King

English:

The Parasitizing King is not a monarch in the conventional sense. He is the singular apex node of the political apparatus, the terminal point where all economic, military, legal, ritual, bureaucratic, and epistemic resources converge. The system is not designed to govern the population but to extract from it. Under the principle of li chu yi kong (利出一孔, "let benefits flow from one orifice"), the king receives all output from society, converting human labor, material wealth, and time into a continuous feed. The Parasitizing King’s power is absolute, not because of charisma or wisdom, but because the entire system is engineered to serve him as a provisioning sink.

2. The Parasitizing Caste

English:

Supporting the Parasitizing King is the Parasitizing Caste, typically around 5–10% of the population in early dynasties. These include bureaucrats, nobles, and elite families who manage, oversee, and legitimize extraction. Their operations include: administering corvée labor, collecting taxes, organizing rituals, controlling education, and enforcing Confucian moral and legal codes. Over successive dynasties, this caste grows, consolidating wealth and power, but their expansion also increases the burden on lower strata. The Parasitizing Caste exists not merely to govern but to ensure the systematic flow of resources upward to the apex.

3. Enslaving Human Livestock and Edible Woman Caste

English:

Beneath the apex, approximately 90% of the population consists of Enslaving Human Livestock and the Edible Woman Caste. This base lived in extreme poverty and exhaustion, often worse than livestock. Men faced harsh corvée labor and taxation. Women, in addition to child-rearing, had to weave textiles, farm during men’s labor rotations, and could be sold if the family lacked resources. The Edible Woman Caste represents the most consumable assets of the system, exposed to literal or symbolic consumption, and forms the structural base of the extraction pyramid. Historical records indicate 388 large-scale cannibalism events across 530 recorded sites in China, demonstrating the extreme pressures imposed by this system.

4. Funnel-History Model

English:

The Funnel-History Model describes cyclical systemic extraction: lower strata (Enslaving Human Livestock and Edible Woman Caste) are continuously drained; resources flow upward to the Parasitizing Caste; when extraction exceeds a critical threshold, peasant uprisings or social unrest erupt; the old parasitic structure collapses; a new Parasitizing King or caste emerges, and the cycle repeats. Dynastic changes are thus predictable systemic releases rather than random events. This model emphasizes that institutionalized ritual, education, and moral legitimation induce the base to accept their exploitation as ethically or religiously justified.

Part 2: Psychological and Cultural Mechanisms

1. Enslaved Parasite Personality (EPP)

English:

The Enslaved Parasite Personality (EPP) describes the psychological profile cultivated by systemic extraction and historical structural incentives among East Asian males embedded in the Parasitizing King–Caste framework. Men with EPP are not merely self-interested; they are structurally programmed by socio-political and familial systems to parasitize others for survival and status.

Key features include:

1. Dependency on hierarchical extraction – EPP individuals are rewarded by proximity to power or access to extracted resources, creating long-term parasitic strategies.

2. Normalization of dehumanization – The social and legal environment trains them to perceive lower strata (including women) as consumable assets, extending to emotional, reproductive, and cognitive labor.

3. Shame-driven compliance and externalized aggression – EPP men internalize social shame yet project it onto subordinate classes, reinforcing the extractive system.

4. Trauma-compatible relational patterns – They unconsciously seek relationships that allow structured extraction, including romanticized abuse cycles, which mirror historical structural violence.

2. Edible Traumatized Servitude Personality (ESP)

The Edible Traumatized Servitude Personality (ESP) defines the psychological profile imposed on women under centuries of East Asian patriarchal extraction. ESP arises from early-life conditioning, sustained deprivation, and structured shame designed to break autonomy and enforce long-term compliance.

Core mechanisms:

1. Systematic boundary erosion – From childhood, girls are subjected to restrictions, shaming, and labor assignments that diminish self-determination.

2. CPTSD formation – Persistent, multifaceted stress creates complex trauma, embedding helplessness, hypervigilance, and internalized shame.

3. Trauma bonding with EPP males – ESP women develop affective attachment to abusive or controlling figures, partially due to romanticized cultural narratives and survival strategies.

4. Normalization of consumption – Socialization teaches that their labor, bodies, and emotions are for others’ use, paralleling historical patterns of literal consumption (e.g., famine, “edible women”).

3. Cultural Embedding and Media Representation

The ESP–EPP dynamic is perpetuated not only by direct familial or state structures but also through literature, music, theater, and film. East Asian media often romanticizes compliance, suffering, and hierarchical devotion in gendered relationships, reinforcing trauma bonding. Examples include:

Classical texts and operas depicting filial women or concubines as virtuous through suffering.

Modern melodramas where female protagonists accept abuse as love, echoing the EPP extraction patterns.

Music and literature emphasizing female patience, self-sacrifice, and endurance, encoding behavioral scripts for the ESP personality.

Part 3: Trauma Bonding, Cognitive Distortions, and Historical Case Analysis

1. Trauma Bonding Mechanisms

The Trauma Bonding between ESP women and EPP men is a historically and culturally structured phenomenon. It is not merely interpersonal; it emerges from centuries of institutionalized extraction and psychological conditioning. Key mechanisms include:

1. Intermittent reward and abuse cycles – Historical records and social norms conditioned women to perceive occasional favor or protection as love or loyalty, despite structural exploitation.

2. Romanticized suffering – Literature, opera, and folklore reinforce the idea that endurance under male authority is virtuous, encoding ESP behavior as culturally desirable.

3. Internalized surveillance and shame – ESP women internalize societal standards, monitoring their own behavior, reinforcing self-blame, and normalizing extraction.

4. Cognitive reframing for survival – Psychological coping strategies such as rationalizing exploitation as moral duty or familial necessity become habitual, leading to normalized trauma bonding.

2. Historical Case Evidence

Historical records show that the Funnel-History Model consistently converted populations into ESP and EPP-compatible roles. Examples include:

Ming dynasty (1368–1644) – Household registration, corvée labor, and heavy taxation ensured that ~90% of the population lived as Enslaving Human Livestock, barely able to feed themselves. Women were simultaneously tasked with raising children, weaving, and planting crops. Many lower-class women were effectively edible assets, tradable or, in famine conditions, literally consumable.

Documented famine cannibalism – Between 500 BCE and late Qing, at least 530 records with 388 large-scale cannibalism events indicate systemic extraction extremities. This reinforces the ESP reality: survival required cognitive adaptation to consumption by elites (EPP and Parasitizing Caste).

Qing elite structure – The Parasitizing Caste numbered ~20–30,000 nobles and bureaucrats, sustaining themselves on the Enslaving Human Livestock base. Extraction was not merely economic; it extended to human essence—emotional, reproductive, cognitive, and moral capital.

3. Cognitive Distortions and Cultural Scripts

The ESP–EPP dynamic was culturally reinforced through cognitive distortions encoded into moral, religious, and aesthetic narratives:

1. Idealization of authority and male suffering – Confucian and Legalist teachings framed male authority as morally or divinely justified.

2. Self-blame and guilt encoding – Women internalized systemic failure, viewing their own deprivation as deserved, aligning with the Parasitizing King’s moral narrative.

3. Normalization of obedience and sacrifice – Ritual, literature, and folklore continuously modeled ESP behavior as virtuous, creating generations conditioned to accept extraction.

4. Part 3 (Extended): Ming Dynasty Parasitic Structure and Funnel-History Model

5. 1. Ming Dynasty Parasitizing Caste and Enslaving Human Livestock

6. English:

During the Ming dynasty, the Parasitizing Caste—including nobles and bureaucrats—numbered approximately 200,000–300,000, forming a substantial extractive elite. Their survival and power were sustained not only by the labor and tribute of Enslaving Human Livestock, roughly 90% of the population, but also by an extensive bureaucratic network requiring constant provisioning.

7. The Enslaving Human Livestock and Edible Woman Caste were thus compelled to support an enormous administrative apparatus. Combined with rule by human discretion rather than law, the lower strata lived in extreme deprivation. Their material conditions were often worse than the 16th-century Atlantic enslaved population: insufficient food, insufficient clothing, exhausting labor, and no personal autonomy. Extraction extended beyond economic resources to human essence—emotional, reproductive, cognitive, and moral capital.

8. 2. Funnel-History Model and Systemic Cycles

9.

The Funnel-History Model describes the cyclical nature of East Asian extractive systems. Population extraction flows upward to sustain the parasitizing caste and elite. When extraction exceeds survival thresholds, widespread social unrest, famine, or rebellion occurs. The system then undergoes collapse, only for a new parasitic king or caste to emerge, restarting the funnel.

10.Historically, the Ming system produced repeated humanitarian disasters, such as famine-driven cannibalism, yet the ideological framing—Mandate of Heaven (天命)—enabled cognitive distortions among the oppressed. The trauma-bonded lower strata internalized their exploitation, rarely holding the system accountable. Modern analysis, however, using historical records, census data, and archaeological evidence, demonstrates the inevitability of high-intensity extraction within this political ecology.

3. Evidence: Cannibalism and Institutionalized Extraction

Between 500 BCE and late Qing, historical records document 530 instances including 388 large-scale cannibalism events.

These events were not anomalies but indicators of a system in which Enslaving Human Livestock and Edible Woman Caste were structurally consumable.

Extraction of human essence ensured sustainable supply for the Parasitizing Caste and King, reproducing obedience and dependency across generations.

Part 4: Modern Continuities, Psychological & Cultural Impacts, and Systemic Toxic Relationships

1. Enduring Influence of the Parasitizing King System

Although the physical institution of the Parasitizing King and its Parasitizing Caste no longer exists in modern East Asia, the structural logic of extraction and hierarchy persists culturally, socially, and psychologically. The mechanisms that enforced obedience, shame, and dependency in historical times have migrated into contemporary norms: gendered labor expectations, filial piety frameworks, elite entitlement, and social surveillance.

The hierarchical psyche—internalized submission of the Enslaving Human Livestock and the Edible Woman Caste—remains evident in social behavior, interpersonal dependency, and the normalization of male-centered power structures. Trauma, exploitation, and internalized obligation have become intergenerational cultural legacies, reinforcing compliance and inhibiting autonomous agency.

2. Psychological Structures: EPP and ESP

Enslaved Parasite Personality (EPP): Historically molded by a system designed to maximize parasitism, East Asian males exhibiting EPP are enslaved by desire, systemically trained to extract and control resources and human essence, often without conscious ethical consideration. Their behavior is a structural product, not merely individual pathology.

Edible Traumatized Servitude Personality (ESP): Correspondingly, women subjected to this system internalize oppression and trauma. ESP manifests as internalized servitude, trauma bonding, and over-adaptation to male extraction, including romanticized perceptions of domination. ESP women often appear compliant, obedient, and self-sacrificial, yet their behavior is a direct consequence of historical, institutional, and familial conditioning.

3. Cultural and Media Reinforcement

English:

East Asian literature, music, and media often normalize ESP behavior while valorizing EPP traits. Traditional narratives romanticize male control, female obedience, and hierarchical structures. Popular songs, TV dramas, and historical novels encode subtle reinforcement mechanisms:

1. Romanticized subjugation: The male dominant / female submissive dynamic is aestheticized, often framed as “true love.”

2. Cognitive distortion: ESP individuals are taught that sacrifice, endurance, and compliance reflect virtue or morality.

3. Intergenerational trauma embedding: Historical trauma is symbolically transmitted via family practices, gender norms, and media archetypes.

These patterns replicate the historical extraction system in psychological form, ensuring the persistence of hierarchy and parasitic dynamics even in modern contexts.

4. Implications for Gender Relations and Social Policy /

Understanding the EPP/ESP dynamic allows scholars, policymakers, and activists to:

Recognize institutionalized trauma dependency in modern East Asian gender relations.

Design interventions to disrupt trauma bonding, encourage female agency, and reduce systemic exploitation.

Analyze historical and contemporary media for reinforcement of parasitic dynamics.

Part 5: Intertemporal Case Studies and Data Analysis

1. Historical Cases of Extreme Extraction Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE): The Parasitizing King Qin Shi Huang implemented li chu yi kong (利出一孔), centralizing all resource extraction. Corvée, taxation, and military conscription turned households into measurable units of provision. Accounts from Han dynasty annals suggest systematic exhaustion of peasants and state-sanctioned ritual sacrifice of humans, particularly during wartime.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE): The Parasitizing Caste included 200,000–300,000 nobles and bureaucrats, sustained by Enslaving Human Livestock. Women, as part of the Edible Woman Caste, contributed reproductive labor, household management, textile production, and sometimes sale in extreme poverty. Economic deprivation, heavy corvée, and moral coercion (Confucian filial piety) ensured internalized submission. Photographs and illustrations from late Ming and early Qing show the extreme poverty and malnutrition of lower classes.

Documented Cannibalism Events: Historical records identify 388 large-scale cannibalism events across 530 locations in China prior to the 20th century. These were not anomalies but outcomes of systemic extraction and famine—a grim confirmation of the institutionalized consumption logic of ENSLAVING HUMAN LIVESTOCK.

2. Quantitative Illustration of Hierarchical Proportions /

Top Node: 1 Parasitizing King per dynasty

Supporting Node: ~10% of population in the Parasitizing Caste

Extracted Base: ~90% in Enslaving Human Livestock and Edible Woman Caste

Resource Extraction Metrics:

Average peasant labor time: 300–400 days/year (corvée + agriculture)

Tax burden: 40–60% of production in peak extraction periods

Nutrition deficit: documented chronic malnutrition; late Ming famine reports corroborate

This pyramid demonstrates systemic inequality: the majority of population provided not only economic and physical labor but human essence—reproductive capacity, emotional and cognitive labor, and cultural compliance.

3. Funnel-History Model Applied

The Funnel-History Model explains periodic systemic collapse and renewal:

1. Extraction Phase: Majority population (EHL + Edible Woman Caste) heavily exploited.

2. Pressure Accumulation: Over-extraction produces famine, revolt, and social instability.

3. Systemic Collapse: Dynasty or parasitic center fails; uprisings release tension.

4. Regeneration: A new Parasitizing King and supporting Caste emerge, often via similar institutional logics.

This cyclicality ensures historical continuity of parasitic structures, even when regimes or dynasties change, reflecting long-term structural trauma embedded in East Asian societies.

Part 5 Supplement: Japan and Korean Peninsula

1. Japan: Tokugawa Shogunate and Peasant Extraction Parasitizing King: The Shogun, while technically subordinate to the Emperor, functioned as the centralized extraction node, similar in logic to The Parasitizing King. Economic, military, and ritual power flowed upward to sustain the elite samurai and bureaucratic class.

Parasitizing Caste: Samurai and bureaucrats, forming roughly 5–10% of the population, were maintained through taxes, corvée, and ritualized tribute from peasants. Their sustenance depended entirely on extracted human essence—rice, labor, reproductive labor, and loyalty.

Enslaving Human Livestock: The peasantry (~90% of the population) endured heavy corvée, taxation, and seasonal famine. They were subject to moral indoctrination and ritual obligations, ensuring internalized submission. Chronic malnutrition and early mortality are well documented.

Edible Woman Caste: Women in rural Japan performed domestic labor, textile production, and agricultural work while their male counterparts served the Shogun. In periods of famine, records suggest women and children suffered higher mortality due to food prioritization for samurai households, reflecting systemic expendability of female labor and life.

2. Korea: Joseon Dynasty Parasitizing King: The Joseon monarch operated as the central node, receiving tribute and labor from Parasitizing Caste elites. Land tenure was centralized via yangban households and enforced through cadastral surveys, ensuring stable extraction.

Parasitizing Caste: Yangban aristocracy (roughly 10–15% of population) controlled land and resources, collected taxes, and administered ritual and civil affairs. Their status was hereditary, and all extraction legitimized via Confucian moral codes.

Enslaving Human Livestock: The majority, commoners and slaves (~85–90%), performed heavy labor on rice paddies, infrastructure projects, and corvée. They were bound to their villages through household registration (hojok) and land allocation systems. Psychological and emotional labor, including filial piety enforcement and internalized shame, ensured compliance.

Edible Woman Caste: Women’s lives were dominated by reproductive labor, household management, textile production, and fieldwork. In periods of famine or taxation crises, women’s expendability was culturally normalized, reflecting structural disposability similar to Chinese contexts.

4. Comparative Remarks

Across East Asia, The Parasitizing King, Parasitizing Caste, Enslaving Human Livestock, and Edible Woman Caste recur as systemic nodes.

Centralization, legal-ritual legitimation, and moral indoctrination create long-term psychological and physical extraction, shaping a structural trauma across centuries.

The Funnel-History Model applies not only to China but also to Japan and Korea: extraction → pressure → collapse → regeneration.

Part 6: Modern East Asian Gender Psychology, Media Phenomena, and Cultural Toxicity Continuation

1. Historical Trauma as Structural Conditioning The centuries-long operation of The Parasitizing King, Parasitizing Caste, Enslaving Human Livestock, and Edible Woman Caste has left structural psychological marks on East Asian populations.

Women, in particular, were subjected to multigenerational systems of psychic and physical extraction, producing widespread vulnerability to complex PTSD (cPTSD).

Internalized shame, normalized deprivation, and ritualized moralization conditioned women to perceive obedience, sacrifice, and invisibility as natural roles.

This historical conditioning laid the groundwork for trauma bonding to contemporary Enslaved Parasite Personality (EPP) males, manifesting patterns where women may rationalize exploitation, emotional manipulation, and extreme dependency in intimate relationships.

2. Modern Media and Literature Modern East Asian music, literature, television, and film often reproduce and aestheticize the historical dynamics of EPP and Edible Traumatized Servitude Personality (ETSP).

Popular narratives depict women who sacrifice, endure abuse, or normalize male dominance as virtuous or romantic, embedding cultural reinforcement of trauma bonding.

This reproduces intergenerational psychic extraction, where symbolic media acts as a conveyor of moralization and obedience, mirroring historical moral-ritual legitimation.

Observed phenomena include the prevalence of “M/S-like dynamics” in romantic depictions, give/taker relational patterns, and the fetishization of female self-sacrifice, all of which are culturally sanctioned continuations of historical enslavement patterns.

3. Social and Psychological Consequences Prolonged exposure to cultural and relational patterns rooted in historical extraction creates measurable psychological phenomena:

1. Trauma Bonding: Women continue to form deep attachments to men exhibiting EPP traits, often rationalizing abuse.

2. Boundary Erosion: Systemic conditioning disrupts intuitive personal boundaries, reinforcing compliance as survival.

3. Cognitive Distortions: Cultural scripts induce internalization of blame, normalization of male dominance, and justification of personal sacrifice.

4. Intergenerational Reproduction: Parenting practices transmit acceptance of hierarchical, extractive gender dynamics, further institutionalizing

5. Policy and Research Implications

Recognizing the historical roots of EPP and ETSP can inform psychological interventions, gender policy, and media literacy programs.

Scholars should integrate Funnel-History Model and Enslaving Human Essence analysis to contextualize structural trauma in contemporary East Asia.

Media critique and reform may reduce inadvertent reinforcement of intergenerational trauma, particularly regarding gendered labor, relational scripts, and romanticization of dominance.

Supplementary Evidence and Conceptual Clarification

1. Historical Ritual and Moral Conditioning

2. Classical texts and institutionalized moral codes reinforced female extraction and psychological control:

Lie Nu Zhuan (烈女傳) celebrates women who die or suffer for filial or spousal loyalty, creating cultural templates of extreme female self-sacrifice.

On Female Virtue (Nü De 女德) manuals codified obedience, chastity, and ritual compliance as criteria for social and spiritual inclusion.

Chastity memorial arches (贞洁牌坊) and shrine restrictions mandated that women adhere to gendered moral expectations to be enshrined in family cemeteries; failure risked being stigmatized as restless spirits or condemned to hellish torment.

Foot-binding culture (裹足) from Ming to Qing institutionalized physical deformation to control women’s mobility and bodily autonomy, creating direct mechanisms for labor and social extraction.

© All Rights Reserved Comprehensive Copyright, Intellectual Property & AI Use Statement

© 2025 Jules Vela. All rights reserved.

This manuscript is an original intellectual work authored solely by Jules Vela and constitutes part of the Dark Disease research and authorship project.

All original theories, conceptual frameworks, analytical models, typologies, terminologies, diagrams, metaphors, classifications, and interpretive structures presented in this work are the exclusive intellectual property of the author.

This includes, but is not limited to, theories such as Cultural Dark Triad Personality, Long-Term Parasitic Dependency Personality, Structural Sadism, and any derivative analytical formulations introduced by the author.

No portion of this manuscript may be copied, reproduced, distributed, translated, adapted, summarized, rephrased, mined, scraped, reverse-engineered, or incorporated into other works or datasets — whether academic, commercial, journalistic, educational, audiovisual, or algorithmic — without prior explicit written consent from the author.

This prohibition explicitly includes the use of this work or its conceptual components in artificial intelligence training, fine-tuning, prompt engineering, or derivative AI-generated outputs.

Publication or dissemination of this manuscript on SSRN or other academic platforms is intended solely for scholarly discussion and does not constitute a waiver, license, or transfer of any intellectual property rights.

。

Any unauthorized appropriation, abstraction, or rebranding of the author’s original theoretical constructs may constitute infringement, plagiarism, or misappropriation under applicable copyright, unfair competition, and intellectual property laws.

For permissions, licensing inquiries, or academic correspondence, please contact:

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!

- 来自作者

- 相关推荐